Supreme Court Kills Tribal Sovereignty Too In Case You Thought It Was Just 'Women' And 'Classrooms Of Kids'

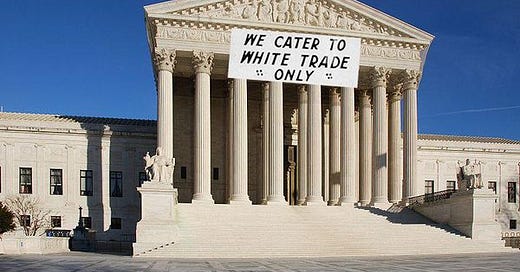

What was that about our nation's history and traditions?

The Supreme Court tossed out decades of precedent (again) Wednesday, granting state governments wider authority in prosecuting crimes on Indian reservations than had been allowed under previous court decisions. The decision, written by Brett Kavanaugh, deeply undercut a Supreme Court decision from just two years ago. In that case McGirt v. Oklahoma, Neil Gorsuch believe it or not wrote a very good decision in favor of tribal rights.

As a result, big parts of eastern Oklahoma, including Tulsa, were declared to still be tribal land, where tribal or federal courts had jurisdiction in cases involving Native Americans. Oklahoma state government didn't care for that, and sued to have some of its prosecutorial power returned. Wednesday's decision accomplished that, at the price of undermining tribal sovereignty and tossing out much of established precedent.

ICYMI: Neil Gorsuch Wrote A Really Good Supreme Court Opinion. Wait, Where Are You Going?

As with other SCOTUS decisions this term, Wednesday's decision in Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta hinged on Donald Trump's addition of one more rightwing jerk to the court. In 2020, Ruth Bader Ginsburg was still around to join the majority in McGirt , but this week, Amy Coney Barrett joined four other rightwing justices to roll back McGirt in a serious way. This time around, Gorsuch wrote a very angry dissent, joined by Justices Elena Kagan, Sonia Sotomayor, and Stephen Breyer.

At issue in this case was a matter that had long been treated as settled law: What power do states have in criminal cases involving non-Indians? (We're going to use that dubious antiquated word more than we usually do, following the usage of the Court and some prominent Native American legal writers. Usage is always evolving, unless you're talking federal courts, right?)

Where We Are and How We Got Here

In cases where a crime is committed on Indian land, the jurisdiction varies on the basis of the identities of those involved: When both the accused and the victim are Indians, tribal or federal courts have authority. If both the offender and the victim are non-Indians, the case is tried in state court. When the accused is an Indian and the victim is non-Indian, the case goes to tribal or federal court. And up until the ruling in Castro-Huerta, the same held for cases where the perpetrator is non-Indian and the victim is Indian. Kavanaugh's decision holds that states will now have "concurrent" jurisdiction and can prosecute non-Native defendants in crimes committed against Native victims on tribal lands.

To be sure, the 2015 case at the heart of the decision is horrible: Victor Castro-Huerta, a non-Native man, was convicted of child neglect after his five-year-old stepdaughter, a member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee, was "found dehydrated, emaciated and covered in lice and excrement, weighing just 19 pounds." The girl is legally blind and has cerebral palsy. The state charged him and convicted him of neglect, and sentenced him to 35 years in prison.

Brett Kavanaugh Dresses Up As Custer

Then, while Castro-Huerta's case was on appeal, the Court handed down its McGirt decision, meaning that the Castro-Huerta case belonged in federal or tribal court. A state court vacated Castro-Huerta's conviction, and he was charged in federal court. He pleaded guilty and accepted a plea agreement with a seven year sentence.

That really appears to have pissed off Brett Kavanaugh, who explained in his decision,

In other words, putting aside parole possibilities, Castro-Huerta in effect received a 28-year reduction of his sentence as a result of McGirt.

Kavanaugh went on to say he believed that happened way too often:

After having their state convictions reversed, some non-Indian criminals have received lighter sentences in plea deals negotiated with the federal government. Others have simply gone free.

So forget all that "precedent" and "our nation's history and traditions" crap the Court has been banging on about lately. This at least partly comes down to Kavanaugh preferring long prison sentences. The state courts are willing to hand down far harsher punishments, and Castro-Huerta really had done something horrible, so too bad for tribal sovereignty.

Claiming that the Court had never taken a "hard look" at the legislation that has so far governed prosecutions in Indian country, Kavanaugh ultimately determined, nah, 200 years of settled law (not settler law, you stop that!) was actually just a big oopsie, and so "the court today holds that Indian country within a state's territory is part of a state, not separate from a state."

Non-Sovereign, Citizenship Questionable

The decision is a major departure from previous understandings of tribal sovereignty, as in it is the exact opposite, and as The New Republic notes, that's exactly what Oklahoma was after.

To get around McGirt, Oklahoma took aim at the root of tribal sovereignty itself. The state argued that it has concurrent jurisdiction to prosecute most crimes in Indian country, meaning that it could do so if the federal government could not or would not. Oklahoma’s challenge was that the practice and policy of the last two centuries pointed in the other direction. In 1832, the court ruled in Worcester v. Georgia that the state of Georgia could not exercise jurisdiction within Cherokee lands because the Cherokee Nation was a separate sovereign.

Other court rulings and laws passed by Congress reaffirmed the principle of tribal sovereignty in criminal cases involving Native Americans, as Gorsuch points out in his dissent, so that

[In] time, Worcester came to be recognized as one of this Court’s finer hours. The decision established a foundational rule that would persist for over 200 years: Native American tribes retain their sovereignty unless and until Congress ordains otherwise. Worcester proved that, even in the "courts of the conqueror," the rule of law meant something.

Kavanaugh's decision threw most of that in the garbage, contending that for two centuries, everyone had it wrong, and that since reservations fall within state boundaries, state law applies on them unless federal statutes specifically say otherwise. States, Kavanaugh wrote, "do not need a permission slip from Congress to exercise their sovereign authority." And now that's the law of the land, tough shit, he likes beer.

Neil Gorsuch, Surprisingly Right Again

In his dissent (starting on page 29 of the SCOTUS decision PDF ) Gorsuch decried the majority opinion, underlining what its betrayal of the principle established in Worchester:

Where this Court once stood firm, today it wilts. After the Cherokee’s exile to what became Oklahoma, the federal government promised the Tribe that it would remain forever free from interference by state authorities. Only the Tribe or the federal government could punish crimes by or against tribal members on tribal lands. At various points in its history, Oklahoma has chafed at this limitation. Now, the State seeks to claim for itself the power to try crimes by non-Indians against tribal members within the Cherokee Reservation. Where our predecessors refused to participate in one State’s unlawful power grab at the expense of the Cherokee, today’s Court accedes to another’s.

The Court's assertion of state power on reservations, Gorsuch wrote, "comes as if by oracle, without any sense of the history recounted above and unattached to any colorable legal authority," and is shot through with "astonishing errors." (We wonder if he will take note for future! Nah .) Ultimately, he said, the Castro-Huerta decision belongs in the "anticanon" of terrible, eventually abandoned decisions likeDred Scott and Plessy v. Ferguson.

'An Act of Conquest'

Native American legal scholars are astonished by the decision. NYU Law prof Maggie Blackhawk said on Twitter that the Court had gone against "hundreds of years of congressional action, against solid SCOTUS precedent, and hundreds of years of history," and that the Court had effectively "become a superlegislature. Precedent, statutes, separation of powers, reason, the rule of law, these things all mean nothing."

Elizabeth Hidalgo Reese, of Stanford Law, called Kavanaugh's decision "an act of conquest. Full stop." It's such an open power grab that she could barely stand to repeat the core betrayal of norms the decision represents.

The right and power of tribes to rule themselves is being dismissed in favor of state power.

Tribes are…I can’t even write it…part of states.

Hidalgo Reese followed that with a brief explanation of why this is important:

For those wondering, “Why is it bad that states can prosecute too?”

Three answers:

1- States/Tribes have a long history of animosity. Fair treatment isn’t a fair assumption.

2- Tribes want to make different laws for their land than states.

3- Many resources are a zero sum game. [...]

4- The feds & states can now blow off responsibility while scapegoat e/o for not prioritizing Indian Country (a difficult and expensive area to police and prosecute).

5- It'll be harder/complicated for tribes to make the case they need more authority to Congress (too many sovereigns in the kitchen already, why would adding another one help?).

There's one potentially bright spot in all this, as Dr. Blackhawk notes: Congress could reverse this very easily with a single brief law.The New Republic explains further: All that would be needed is

a single-sentence law that explicitly blocks concurrent jurisdiction. (Kavanaugh mocked Gorsuch for writing that sentence in the dissent but did not dispute it.)

But that needs to happen soon, before the Court decides to erode tribal sovereignty any further in upcoming cases.

[ Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta / NYT / New Republic / Maggie Blackhawk on Twitter / Elizabeth Hidalgo Reese on Twitter]

Yr Wonkette is funded entirely by reader donations. If you can, please help out with a monthly $5 or $10 donation and we'll keep bringing you the latest on our collapsing Republic, plus fart jokes.

Do your Amazon shopping through this link, because reasons .

Ta, Dok. Yes, I expected to be saying ta, Liz about this one. I am furious (again). I am sure that beneath this decision is corporate money saying it's okay to mine for e.g. uranium on tribal lands and poison their water, soil, and air. Actually, furious only begins to describe how I feel about this. I have friends who are First Nations within several states in the U.S. and they have fucking suffered enough.

Leo (VP of Federalist Society) has been plotting for years to take over SCOTUS. He's a poisonous spider; full of corrosive venom for our democracy and ensnaring the unwary in his sticky webs of deceit, hatred, fanatacism and lies.