Sundays With The Christianists: Ernest Hemingway Will Lure You To Hell Or Key West

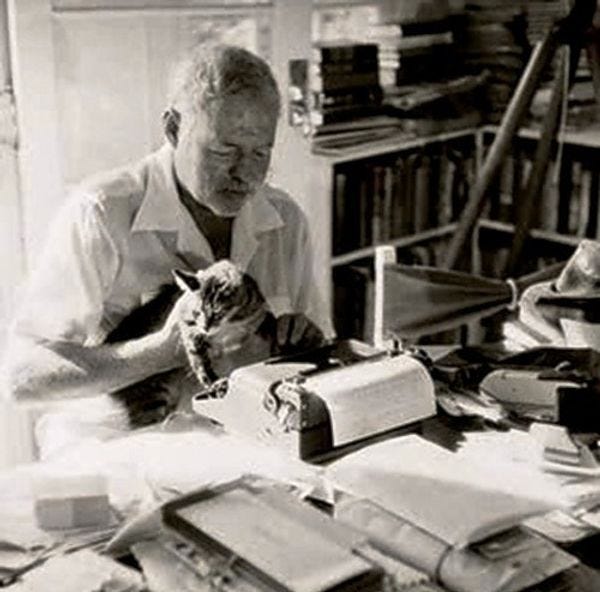

Is Ernest Hemingway still a big deal? We guess he's still a big deal, still in anthologies and literature classes, although his hyper-macho manly creed of manliness makes for pretty easy parody. He's certainly a big deal to rightwing radio preacher and homeschooling advocate Kevin Swanson, who lets Hemingway carry half the burden of representing all of 20th-century literature in his premature report on the death of Western civilization, Apostate: The Men Who Destroyed the Christian West (the other representative of the century is John Steinbeck, who we'll get to next week).

Swanson's quite certain that true Christian faith was pretty much on its last legs by the early decades of the 20th century: American institutions, especially schools and the churches, had been thoroughly corrupted by humanism and godlessness, by "the ideas of the Renaissance and the Enlightenment," which, you need to remember, are bad things because they supplanted the Bible as the focus of all thinking. For most Americans, "Church attendance had become a cultural observance rather than an act of religious devotion. For the most part, the mainline denominations had little to do with advocating a Christian worldview."

Needless to say, that cultural decline was reflected in and advanced by literature, and there's not much good that Swanson sees in anything published after 1900 (or before, come to think of it). With that weird phrasing fundamentalists just seem required to use, Swanson says, "Modern literature represents an increasingly aggressive opposition to God and His law order." He explains that secularist attacks on God's law order was first targeted toward the elites, the better to bring down civilization altogether:

If a civilization will collapse, it is the pillars of the social order that must come down first. As should be expected, recent surveys indicate that 87% of college professors call themselves “liberal,” 70% support homosexuality, and 80% support abortion on demand. Predictably, these surveys identify the Literature Department and the Religious Studies Department as the most liberal elements of academia. The universities produce the acidic solvents necessary for the corruption of the pillars of society -- the future leaders for church, state, and academia. Eventually, the super structure comes down, but only after the corrosive ideas work their way into the mass culture...

Swanson warns, once more, that Christian students need to be especially careful when reading modern literature, since it is designed to corrupt them and destroy their faith:

It is hard to recommend any of the literature produced in the 20th century for the Christian literature student. Most of the “best” literature used in high school and college classrooms is virulently anti-Christian, nihilistic, suicidal, and hopeless. It is perverse on the face of it -- the language is defiling. If the readers come too close, they will find themselves in fellowship with the “unfruitful works of darkness” (Eph. 5: 11).

He follows this fretting with a line that almost makes us wonder, again, if the entire book isn't just pulling our leg:

This introduces a catch-22 of sorts.

Nah, not a reference -- he didn't capitalize it. The catch-22, by the way, is that truly understanding literature requires "close communion in order to understand the content and fully appreciate its emotional tones and its several layers of thought." Ah, but Swanson warns, "the devil is a good writer, and ungodly men often produce excellent literature in form," and so "the Christian reader must consciously hold the ideas at arm’s length, so as not to commune with the unfruitful works of darkness, or meditate long and hard on things that are not true, not lovely, and not pure (Phil. 4: 8)."

Dude, if there's any kind of solution, then that's not even a Catch-22.

Swanson adds that it's really hard to "to identify the most significant American and English writers of the 20th century" because one finds "only minor differences betwen [sic] them in terms of their worldview perspective and influence" -- which is to say that they were all ungodly and horrible. He has a somewhat odd notion of the modern literary pantheon:

The “greats,” F. Scott Fitzgerald, John Steinbeck, Ernest Hemingway, and J.D. Salinger were all committed to set a destructive course in their writings. The literary expression was fragmented, chaotic, and directionless. When they communicated clearly, they wrote of suicide, isolation, drunkenness, apostasy, fornication, mental illness, and profanity.

Just those four guys? Discuss amongst yourselves. Swanson does acknowledge that there were a few Christian writers who resisted the overwhelming trend of the century, like T.S. Eliot, C.S. Lewis, and J.R.R. Tolkien, but sadly notes that "Christians don’t win Nobel Prizes from apostate institutions." But even though you'd be challenged to find a literature anthology that didn't include Eliot, he almost doesn't matter to Swanson, because his goal is to "[follow] the flow of the river of Western civilization all the way downstream and over the Niagara Falls into oblivion," even though there may be "the occasional diverting stream that was provided by Christian thinkers and writers[.]" With civilization collapsing, it's of little comfort that Eliot wrote a poem about the Magi.

And so, since he's pretty sure that all 20th century writers are equally corrosive, Swanson finally gets to Hemingway, who, unlike Nathaniel Hawthorne or Mark Twain, does not get overtly accused of having been possessed by demons. Maybe Swanson just figures it's self-evident. The real surprise in this section is Swanson's attack on the turn of the century's evangelical movement, whose theological underpinnings he believes were too shallow:

While some of those who were converted in revival services held strong to the faith, apostasy came easily for their children. The generational roots never ran very deep in this sect of the Christian faith.

We're not sure how much of that is genuine theological criticism and how much of it is just a convenient way of explaining why Ernest Hemingway, whose parents were devout revival-meeting converts, turned out to be so very evil. We suspect it's a sincere criticism, since the only people Swanson detests more than secularists are Christians who are Doing It Wrong.

Swanson's biographical sketch of Hemingway is largely cribbed from James Mellow's Hemingway: A Life Without Consequences, but we won't hold Mellow responsible for anything Swanson comes up with. We learn that, as a teen:

Hemingway produced several shockingly pornographic stories, pouring out a torrent of foul language previously unheard of in American literature. He was a true pioneer in sexually decadent expression from the beginning of his writing career ... His rebellion comes across as radical, pathological, even dangerous or sinister. As far as biographers can discern, he experienced no pangs of guilt whatsoever about his debased thoughts and expressions, no second thoughts. This apostate plotted his course early in his life and never looked back. At 18 years old, he was done with church ... His life henceforth was filled with fornication, adultery, and divorce. Throughout his lifetime, he routinely took God’s name in vain and seemed to favor abusing the name of Jesus Christ.

And here, Swanson pauses to remind us with a Bible verse that God is quite displeased with having His name taken in vain. Good to see he backs up his arguments with citations.

Hemingway was also obsessed with "patricidal rebellion," and he even cursed his mother, who in turn was appalled by his degeneracy. We learn that in 1949, Hemingway even "referred to his mother as a female dog and publicly stated, 'I hate her guts.'" Swanson is pretty impressed by just how well Hemingway fits Matthew 15: 4's description of "the incorrigible youth":

“But [Jesus] answered and said unto them, ‘Why do ye also transgress the commandment of God by your tradition? For God commanded, saying, Honour thy father and mother: and, He that curseth father or mother, let him die the death’” (Matt. 15: 3, 4).

Whether or not the civil punishment is warranted, the general principle must not be missed. Jesus Christ takes the Fifth Commandment very seriously, and He strongly underscores the egregiousness of Hemingway’s crimes. When a young man takes it this far, he walks over a very big line, and the repercussions upon society will be significant.

That's pretty daring of Swanson to hedge even the slightest on whether we should obey the commandment to stone our unruly children to death. Where do we report him for backsliding? But you have to admire his reasoning: Ernest Hemingway didn't honor his father and mother, Ernest Hemingway was an influential writer, and so Ernest Hemingway gave us youth rebellion (and for all we know, Charles Manson, why not?). He goes on for several paragraphs about Hemingway as an avatar of rebellion against the Fifth Commandment, and the inevitable consequences:

Breaking the Fifth Commandment is the heart and soul of a cultural and social revolution, and it is usually the requisite ingredient for bloody, political revolutions as well. It is the undoing of a civilization. The only thing that keeps social systems together is the honor of parents and grandparents. This is a principle which even pagan societies understood.

Among the results of this degeneracy, Swanson lists "the rock rebels of the 1960s and 1970s," drug culture, shacking up, fatherlessness, homosexuality, abortion, and the definitely-gonna-happen "80 million elderly soon to be euthanized (2020s-2050s)." Make sure you get that in your calendar.

Eventually, Swanson gets back to Hemingway and his writing and discovers that Hemingway is also not a Christian there, either: "Ernest Hemingway’s stories are hopeless. They reflect a metaphysic that disallows all meaning and purpose to life and death." And here we thought they were about fishing.

You might think that Hemingway's experiences in World War I might merit a mention as having contributed to his bleak worldview, but Swanson literally says nothing about that little bit of civilization-destroying between nations convinced that God was on their side. And needless to say, Swanson is quite pleased to report that not only did Ernest Hemingway kill himself, so did his father -- whose "faith proved shallow and fading" -- and his granddaughter Margaux, proving that the entire family was afflicted with "a retroactive apostasy that played itself out over multiple generations." Depression? No such thing. "Retroactive apostasy" is the problem.

As for Hemingway's actual work, Swanson limits himself to a discussion of The Old Man and the Sea, and an explication of the novel's nihilistic vision:

His humanist ideology is clearly explained when the fisherman claims that man is not made for defeat. He says, “A man can be destroyed, but not defeated.” That is, a man lives his life to the fullest when he fights to the bloody end. According to Hemingway’s hero, the purpose of life is to attempt to strive for mastery over the environmental forces that surround the man, despite the fact that such efforts always prove to be a lost cause. Man always dies in the end.

In contrast, Swanson notes, Christians love a good fight, but not against anything so mundane as nature:

We are in a spiritual battle against the world, the flesh, and the devil. For us, there is more to life than the natural, physical world; there is the supernatural and the spiritual . Therefore, the stakes are much higher for us than for the old fisherman, as we battle in God’s arena. It is a glorious battle and there is eternal value for the combatants who take the side of the Kingdom.

Swanson really gets into this spiritual battle stuff, and whips himself up into a fine Passion of the Christ bloodlust, sounding a bit like he belongs on the Group W bench:

Our strength comes from God, and yet we struggle with all of our might out of sheer love for God in the conflict. Though our faces drip with blood and our hands are chafed to the bone, there is joy in the battle and hope in our hearts as we fix our eyes on the day of consummation when the battle will be won. Then our great Captain will greet us at the gates of the heavenly Kingdom with the words: “Well done, thou good and faithful servant.” This is what renders the Christian life true meaning and eternal purpose. What a contrast to the nihilist worldview of a man who committed suicide!

You just know Kevin Swanson was rock hard there.

Anyway, the story is about struggle, but it's meaningless, since the old man fights the fish in a meaningless world that can bring nothing but death: "He wants to argue for a purpose in life, but his universe is indeterminate and material. There is no possibility of purpose in a purposeless universe." Like most books, it would have been a lot better if the Old Man had repented his sins, which is how all good fiction should end. But Hemingway "has no confidence in the resurrection," as he proved when he shot himself.

We bet that Kevin Swanson is a heck of a lot of comfort when he does pastoral counseling.

Apart from Old Manand an endnote's mention of "Hills Like White Elephants" -- in which Swanson claims Hemingway "commends abortion," which kind of misses the point -- there's not much else about Hemingway's work here. Frankly, the biggest surprise for us was that Swanson doesn't mention one of Hemingway's most blasphemous passages, from "A Clean Well-Lighted Place," where the old waiter murders the Lord's Prayer and the Ave Maria both:

It was all a nothing and a man was nothing too. It was only that and light was all it needed and a certain cleanness and order. Some lived in it and never felt it but he knew it all was nada y pues nada y nada y pues nada. Our nada who art in nada, nada be thy name thy kingdom nada thy will be nada in nada as it is in nada. Give us this nada our daily nada and nada us our nada as we nada our nadas and nada us not into nada but deliver us from nada; pues nada. Hail nothing full of nothing, nothing is with thee.

Why leave that out? Maybe it was too Catholic, with that rosary-pushing. Perhaps Swanson just didn't want too much contact with Hemingway, so he avoided this very worst example. Or maybe it's because the story ends with the old waiter ordering a cup of coffee like some damned Unitarian.

Next Week: A chapter on John Steinbeck by a preacher who doesn't seem to have read The Grapes of Wrath.

Amazon ranks it near the bottom of the whole religion/faith/woo category . . . and you know there's a ton of worthless dreck in that category.

Unless you have one of those "bundles" of joy.