Sundays With The Christianists: Satan Done Wrote 'Huckleberry Finn'

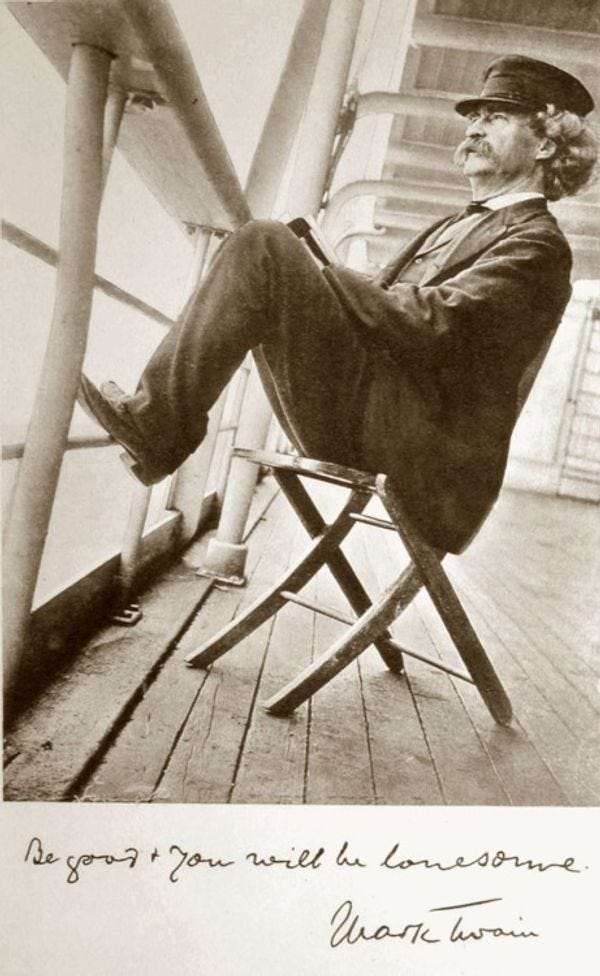

We're beginning to get the feeling that Kevin Swanson, the Colorado radio preacher and homeschooling advocate, doesn't like America very much. Just maybe. His ebook Apostate: The Men Who Destroyed the Christian West is mostly a rant about how America would be a much better place if only it were post-Reformation Europe, or at the very least if it were Puritan New England before they allowed in all those Quakers and voted for Dukakis. Mark Twain sits at the top of Swanson's Public Intellectual Enemies list, because, as Swanson says,

if you believe that God is real and Satan is real, then Mark Twain was a dangerous man. He may have been a talented writer, and he may have enthused hundreds of millions of people around the world, but he set a bad trajectory for himself and his readers during the great apostasy of the Western world. Mark Twain hated God, and he led the masses into apostasy.

We have to say that we were a little disappointed in Swanson's chapter on Twain. Oh, sure, there's the suggestion that Samuel Clemens consorted with demons, because how else could he have written Letters From the Earth in the voice of Satan himself? But when he finally gets around to discussing Twain's greatest work, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Swanson goes off on an insane discussion of why the novel's attack on slavery is actually very unfair and inaccurate, as we discussed last week. [contextly_sidebar id="qZYiSVeATgkdcbcBhKl84x4SB6PBTCng"]

The gist of that digression was that the institution of American slavery was actually very different from the kind of slavery practiced in the Bible, so how dare Twain mock Southern Christians for supporting slavery since real Christians would never support such a thing? It was certainly an entertaining mélange of WTF, but it takes up roughly half of Swanson's Twain chapter and we'd been hoping to learn a lot more about how Twain was doing the Devil's bidding. Even so, once he dismisses Twain's refusal to appreciate the intricacies of what Kevin Swanson thinks were important differences between slavery in the Bible and how Americans actually did it, he finally explains the deep moral offenses of Huckleberry Finn:

Mark Twain wasn’t interested in discovering what the Bible really said about slavery or anything else. At heart, he was a humanist. It was already a decided fact in his mind. So he took advantage of a weakened faith, created more straw men, and proceeded to take it apart piece by piece, all the while presenting his “better ethical system” to the world. All humanists are moralists at heart. They loudly claim that their self-concocted moral agendas will produce more good in the world than the old Christian order. Of course, just the opposite happens.

In Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain puts Huck solidly between the horns of a dilemma. Either he must support slavery or he must oppose the Christian God and go to hell. At first, Huck thinks he should turn over his escaped slave friend, Jim, to the authorities; but then he decides against it (Chapter 31). In this pivotal scene from the book, Twain depicts the American Christian God as a pro-slavery villain who would have Huck surrender his friendship for the cause of slavery. The utter contempt Mark Twain held for the Christian God is inescapable.

We think Swanson has that just a little bit off: Huck isn't rejecting God: He's rejecting all of the nonsense he's heard about God from legions of good decent church-goers (with their mean, pinched, bitter, evil faces). It seems like a useful distinction, though not one that Swanson would be any more pleased with: God is pretty much AWOL from Huckleberry Finn from the get-go. Sure, the Christianity that Huck rejects is a caricature; Swanson simply rejects the proposition that Twain's satire has a legitimate target. After all, on Planet Swanson, real Christians don't believe in slavery. Nevertheless, it's fun to watch Swanson sputter at just how unfair it is of Twain to have made Huck such a sympathetic character:

As Huck adamantly rejects thin-coated, hypocritical Christianity, the reader will almost inevitably want to take his side. By the end of the story, we get the message loud and clear: Huck is a good old boy, and Christians are simple-minded and stupid. As is typical with the individualized American religion, Huck makes up his religion as he goes along; it is sometimes dualistic (he believes in a good god and a bad god) and sometimes agnostic. As the story plays out, Huck is particularly given to the sins of cursing, blasphemy, dishonor of parents, cross-dressing, stealing, and lying.

Yes, cross-dressing. You knew he'd get that in there. Surprisingly, Swanson doesn't find any cannibalism in the novel. And by some miracle, Swanson appears never to have read Leslie Fiedler's notorious essay "Come Back to the Raft Ag'in, Huck Honey!" (1948), so we are at least spared Swanson's condemnation of the novel's terrifying homosexual undertones. Even so, he does find plenty of sin as it is, mostly in the form of Huck's self-constructed morality, which is of course anathema all the way down:

Perhaps the most appalling part of Huck’s character is his readiness to break God’s law without regret. His forthright disobedience of God’s law, his apparent lack of conscience, and his audacious rebellion against God was appealing to 19th century readers. This was how our nation lost its respect for God’s law and God’s judgment.

Again, this is a dubious proposition, given the general absence of anything like a clear vision of "God's law" in the novel -- for Twain that's a feature, for Swanson, it's a Beelzebug. But no matter; Swanson is eager to explain the fix that Mark Twain personally got us into:

Of course, the stars of today’s world break God’s law with abandon, but before any of these celebrities showed up there was Huck Finn. People emulate their heroes. When the humanist cultural power centers manufacture heroes who exemplify godless, immoral lifestyles, hundreds of millions of people follow them. Huck is such a hero. Today, the cultural machine cranks out the new heroes every year or two, including such familiar names as Michael Jackson, Eminem, Hannah Montana, Katy Perry, Carrie Underwood , and Taylor Swift. Some of these celebrities begin with a little respect for Christianity, but they quickly demonstrate their true commitments, as they go on to promote homosexuality, serial fornicating hook-ups, and other assorted iniquities.

Swanson doesn't quite explain how he gets from Huckleberry Finn to Taylor Swift; nor does he seem especially worried bout minor distinctions between fiction and reality, like the fact that "Hannah Montana" is not a real person.

Swanson finds just about everything in Huckleberry Finn blasphemous, and we suppose maybe it's a fair cop:

Within the first pages of Mark Twain’s classic, Huck mocks the idea of God’s judgment and the Christian doctine of hell when he tells Miss Watson that he wishes he was in hell. No wonder H.L . Mencken and Ernest Hemingway were so appreciative of this groundbreaking work.

You may remember that blasphemous passage, in which Twain plays Eternal Damnation for laughs. Swanson doesn't quote it, perhaps because it's simply much more fun to read than Kevin Swanson's prose:

Then she told me all about the bad place, and I said I wished I was there. She got mad then, but I didn't mean no harm. All I wanted was to go somewheres; all I wanted was a change, I warn't particular. She said it was wicked to say what I said; said she wouldn't say it for the whole world; she was going to live so as to go to the good place. Well, I couldn't see no advantage in going where she was going, so I made up my mind I wouldn't try for it. But I never said so, because it would only make trouble, and wouldn't do no good.

Yr Wonkette assumes no liability for any eternal harm to your immortal soul resulting from exposure to this passage.

Ultimately, Swanson sees the pivotal moment in the book, Huck's declaration that if it's a choice between betraying Jim and going to hell, then he'll take hell, as a supremely tragic moment, not as the ironic triumph of genuine love over a twisted moral system. Referencing a character in The Pilgrim's Progress who insists that he is beyond salvation and turns away all attempts to help him, Swanson laments that Huck really, truly has chosen the Dark One -- and has taken all of American Culture with him:

All in all, this makes for a rather unhappy story, when we realize that we are actually visiting with “the Man in the Iron Cage.” At this point, the story is no longer entertaining. We cannot fellowship with the character, but shall we pity him? Shall we weep over him? Certainly it is hard to laugh while he works his merry way through the gates of hell. At the least, we hope that the readers of this dreadful story will not identify with Huckleberry Finn in his skepticism. Alas, that is typically not the case in American high schools and colleges.

Just in case there was any question that he's a humorless git, Swanson seems to take every joke at something less than face value, refusing to acknowledge any ironic intent in the passages of Twain that he does cite:

[Huck] dislikes his conscience because he thinks it is irrational. “Whether you do right or wrong, it still attacks you,” he complains. In the end, Huck settles for pragmatism as the best ethical course. He says, “I don’t care about the morality of it” (Chapter 36). Both Huck and Tom agree that the ends will justify all means to accomplish the goals they have in mind, and for these boys, the means usually involve an appreciable measure of stealing and lying.

If you really want to nitpick, Huck actually says he doesn't "care shucks for the morality of it," and here, it's in the context of the closing chapters' game-playing with Jim's freedom, where Huck's concern for Jim is overridden by Tom's insistence on constructing a satisfying adventure narrative, so, you know,irony.Never mind. Huck and Tom are just amoral humanists, and they should turn to Jesus instead of being in a Twain novel: "Although he does feel a little guilt here and there, Huck refuses to seek redemption in Christ," which is apparently how all good fiction should end. We'll admit that it would have made the climax of Die Hard more Christmassy.

Swanson is very pleased with his close reading of the novel's final words -- not the "lighting out for the territory" bit, which we're sure he could have turned into Huck's vow to create his own flawed, humanistic moral code like some kind of damned Unitarian -- in which Swanson finally thinks he's discovered an irony that underlines just what a cunning deceiver Mark Twain is:

Fittingly, the story ends with: “Yours truly , Huck Finn.” There is a dark irony contained in these last words. Throughout the narrative, Huck has proven himself to be the consummate liar. He makes up new stories for almost every person he meets. By the end of the account, there is no way to know whether or not Huck has just pulled the wool over the eyes of the reader as well as the characters involved.

Ooh, lit crit! Hey, why would Huck find lies useful in a world filled with adults who think that slavery is a fine moral thing that's justified by the Bible? Also, shut up, Swanson already told us the Bible does no such thing, so that doesn't count. Ah, but who is the bigger liar? Huck Finn, or his creator, who turned his back on his Creator?

Of course, the story is fictional but what about the story behind the story? At the beginning of the novel, Mark Twain opens with these words, “This book was made by Mark Twain, and he told the truth, mainly.” But if the novel justifies lying for the protagonist, what can we say for the author? What about the worldview behind the fiction? What about the mockery of Christianity or the agnosticism of Huck? Was all this true, mainly? Or does Mark Twain prevaricate, equivocate, fabricate, and calumniate as much as Huck lies? Mark Twain may have been a great writer, but he was also an expert liar. Pilate asked a very important, fundamental question at the trial of Lord Jesus Christ. “What is truth?” Mark Twain abandoned the only possible source for an absolute truth -- divine revelation. Without the truth of God’s Word, we are forever lost in a snowstorm in Antarctica when it comes to discerning what is true and what is false. When Mark Twain rejected this truth, all he could do was play with lies. That is what he did, and he was good at it.

Oh, oh, and you know who the Father of Lies is? Dayumm, Kevin Swanson is smart, Mark Twain is dumb, and we now pledge to never read fiction again, because it is full of lies.

Or maybe Swanson should simply have paid attention to Twain's epigraph to Huckleberry Finn:

NOTICE

PERSONS attempting to find a motive in this narrative will be prosecuted; persons attempting to find a moral in it will be banished; persons attempting to find a plot in it will be shot.

BY ORDER OF THE AUTHOR

Per G.G., Chief of Ordnance.

When students in littachur classes used to protest that Twain was telling us that we shouldn't try to find meaning in his book, we always just chuckled and told them they still had to write their analysis papers, but we're starting to wonder if perhaps Twain presciently had Kevin Swanson in mind.

Hm. The raw probability is pretty high.

Back in the late 70's - early '80s I was the product manager for, among other things, an 8-bit microcontroller that was fairly widely used in new-fangled gasoline pumps. We got to do an awful lot of tech support as the manufacturers tried to figure out how to rewrite or patch the ROMcode for their programs, because of course some of them had not thought to allow for a per gallon price greater than 0.999.

As the price crept higher, the fun escalated, as the station-owners, who had already bought and installed uC-controlled pumps became vociferous.

In the long run, of course, it worked out to benefit the pump manufacturers, because (once they had patched the code) it increased the attractiveness of a replacement pump.