Our Man In Havana

Fidel Castro died Friday night, aged 90. We offer you here a story we wrote some years ago, when we were living in Los Angeles, unemployed, before we'd bought a job at your Wonkette. It is a pretty story, we think.

Semper Fidel

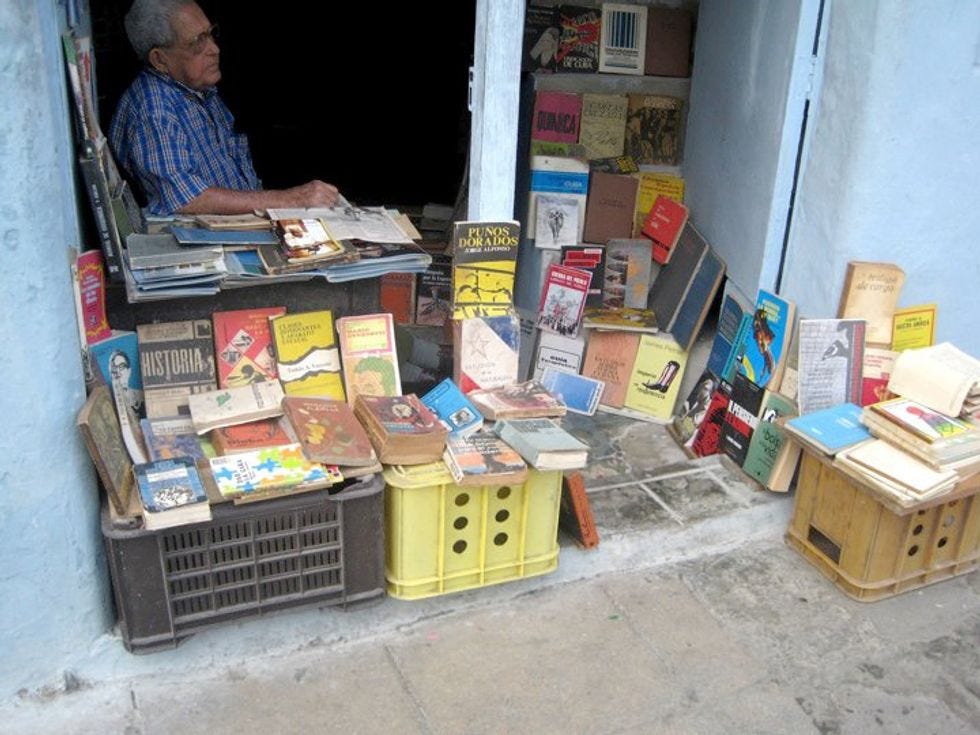

It is foreign, and we are on a very fancy bus, 13 or 17 of us or so, writers and our lovers and a few nice neighbors who thumbed a ride with us from Orange County, California, to Havana, Cuba. We are gawking out the windows at a land free of any advertising except exhortations to educate your children and pictures of the nation’s heroes. Cuba loves its heroes, its Comandante Che and its number one hero of all time and forever, Jose Marti, who was neither a general nor a baseball player but a writer , and that’s just weird. We are looking at the open spaces, almost agriculture-free but for a field or two here or there, and the 1960s Soviet concrete monoliths, and the God-sized portraits of Che.

And then we come into Havana itself, taking a roundabout way that brings us past stately homes on the Avenue of the Presidents (but in Spanish), only a couple of whom have statues because they turned out to be so corrupt and lame, and the Cuban people said, “Fuck! Enough with statues of the presidents already, let’s just sculpt some more of Jose Marti!”

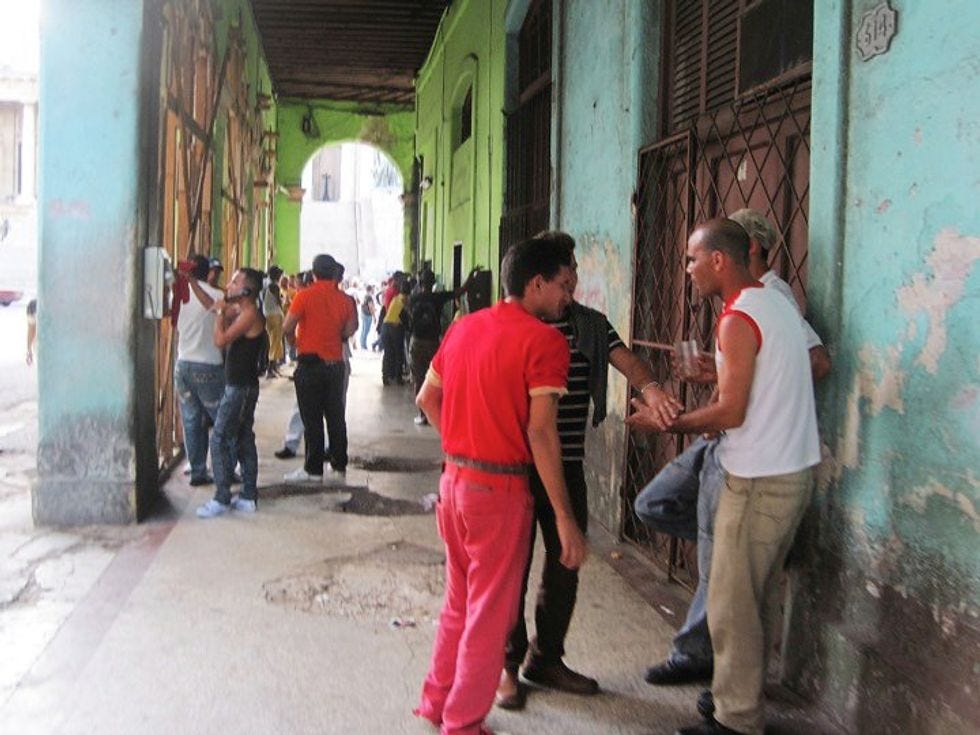

And Havana is so dreamy and beautiful and different — different from our homes, from anyplace we have been, and from how we thought it would be. It is massively crowded, 2.2 million people squashed into a city you could walk across in not so very many hours. People wait in bus lines of many dozen; occasionally a lady will stoop to scratch the ears of a stray dog, which are everywhere, small and scrawny and mellow, just hanging out on the curb waiting for a kindness. Rotating clinics bring them in for desexing and the occasional worming, and then set them free.

The buildings are so beautiful, most shabby and falling apart, and it seems like 90 percent of them were at one point many years ago painted in one or another shade of Caribbean blue, the remaining shards of paint job still glowing and vibrant, and they range from the Spanish colonial cathedrals of the Habana Vieja (old town); to Centro Habana’s buildings that could have stepped out of New Orleans’ French Quarter; and to bungalows that could be in Santa Barbara or Hollywood right this very minute, but they’re in our neighborhood, Vedado, instead. A ways away are a couple of sort of suburban sections of town, Miramar and Playa, and their buildings could be among the more modest homes in Bel Air.

On the crowded streets of Vedado, people pick us out as tourists immediately, and not even because of our shiny, plush bus. First, we are with a big group of old people (Gilda, an urban planning professor at UCLA, is racked with hilarity that we’re sort of somewhat divided by age, with “the youngs” reaching all the damn way up to 49, which I believe is how the Orange County Young Republicans keeps its membership numbers up too, and the olds from 49 on).

Second, my boyfriend is Japanese, which makes him maybe the only Chinaman on the entire island, and everywhere we go for a week, people will call him out: “Chino, ssst, Chino!” they say, while they are trying to sell him cigars in the park, and I swear I heard one man call to him “Ching Chong,” but Paul said the guy called him “Jackie Chan” instead, and at one point, an entire busload of schoolkids hangs out the windows shouting to him, chino, chino, until finally he gives in and waves. (I call him mi chino guapo the rest of the week, and everyone laughs—especially the Puerto Rican rock stars at our hotel, because a “chinito” seems to be one who takes it in the ass.)

Oh, and third, I’m not dressed like a whore. Las Cubanas are tottering miles in gold fuck-me-pumps and shoving their shit into so many five-pound bags, and not only are all items of clothing several sizes too small, bellies flopping magnificently, but in many cases they’re denim, too, and I simply can’t fathom how they’re going to peel them off after walking a mile or two in muggy 80-degree heat. After seeing the way people were blinged in the airport, the other girls and I decided we needed to step up our game, so I hauled my bosoms out and plated them up, and found some pants that would hang beneath my own magnificent belly, but most of the time I wear long skirts for tropical ease and comfort, and I figure Habana’s people feel sorry for me. Poor thing, is she a Mormon? we imagine them wondering. She might be all right if she just got her ass out!

Paul and Rebecca Go for a Walk

Our group is meeting at six to go to a jazz club, so Paul and I disappear hours earlier so we won’t have to join them. The only thing we would rather do less than go to a jazz club is tour a cigar factory, which people will be doing too. Habana Vieja is the proper tourist destination, an easy 20-minute walk along the seawall (the Malecon) from our hotel. We cut inland, through Centro Habana, thinking it will be easy to spot the Capitolio’s dome to keep us on track, but the streets are so narrow and the buildings so high we can not see it at all.

As we walk, we gape at the practically war-torn buildings, such beautiful bones, their decay the most beautiful thing about them. They stretch back hundreds of years, some with ironwork, some with rebar. People’s apartments are situated right at our elbows; we look in and see the TV and couch, the linoleum flooring. They are dark, and low-ceilinged, and must be very hot, and Paul starts to walk into someone’s house to take pictures. “I thought it was an alleyway,” he lies, when I pull him back out with a “BABE! That’s someone’s HOUSE!” As if we aren’t conspicuous enough.

And as we go on, looking to spot the Capitolio, I miss my mama ferociously. She should be here with us. She loves Fidel, like, romantically; she feels about him as most right-thinking women feel about George Clooney. She would like to kiss him, on the mouth!

She would like walking with us, through Centro Habana where the people live, not the twee Old Town, which has been restored and rehabbed and is indeed beautiful and where people live too, but it was restored and rehabbed for us: for Canadians and Europeans and maybe a few yanquis, so we would have a place to feel luxurious as we drank our mojitos on the hotel roofs. She would be a companera. She would not be interested in the rum factory tour, or La Floridita, a monstrosity of a tourist trap where Hemingway once presided. She would like the rooftop bar at the Hotel Ambos Mundos in Vieja, because the view across the channel and of all old town below is romantic and there is nothing wrong with having a nice place for a drink or an espresso.

And she might even like herself a nice room at the Hotel Nacional — there is nothing wrong with having a nice room, maybe, although I bet she would have been really happy at one of the home-based casa particulares — but she would like best the part of Havana where the tourists don’t go, where only people live, and where very few people try to walk into your house, camera snapping. She would like to stop and buy a cola out of a window in the wall, too, the way the companeros do, but I’m not sure you’re allowed to buy them with tourist money.

Rico y Suave

We are not used to living four-stars like this, to being the muy rico ones. Paul and I have both been out of full-time work for more than a year since our newspaper shut down, and we scrimp like Depression grandmothers who wash and reuse aluminum foil before stuffing you full of Werther’s sugar-free mints. Before leaving Los Angeles, I’d even felt the need to have a talk about how we must tip well and often, in case he started to act like a Young Republican or someone from France. We will bring loads of consumer-good gifts, two suitcases worth, for anyone we meet, and we will not be in love with our money.

We are the muy rico ones here in Havana, and I don’t feel guilty, as I did when the neighborhood children in our Long Beach ghetto were goggle-eyed that my son and I each had our own room, but I do feel a little defensive. When the coco-taxi driver smiles at us, “Ah, U.S. Muy rico!” I start to explain that we’re not, no trabajo uno ano, before I shut my fool mouth. We are staying a week at the Hotel Nacional de Cuba; we are rich enough for that, even without work, and that’s probably even worse.

It is a thrill ride, she favoring the horn over the brake, and I appreciate (without understanding word one) the laughing conversation she has with the motorist next to her when she at last has to stop for a red light. “Amigos?” I ask her. “No,” she shrugs, in Spanish she breaks down for me into the fewest words humanly possible. “In Habana, [something something] amigos rapido!”

The Hotel Nacional is a grand Deco/neocolonial edifice from the ’30s, where army clerk Fulgencio Batista laid siege to the government that came before him, and where Lucky Luciano held an infamous mobsters’ summit to divvy up the city. With grand verandas teeming with waitstaff for an attempt at full employment, it’s the only hotel on the island of Cuba that’s also a national landmark. People write in to TripAdvisor to bitch that their carpets are spotty, the staff is unfriendly, and the free breakfast’s no good. But on the sixth floor—the Executive Floor—there is a 24-hour lady at the desk to answer your pidgin-Spanish preguntas (she speaks English, but is amused to hear you try), and a private breakfast that offers odd foodstuffs, and an army of ladies leaving your large, gracious room with views to weep for very clean. You can kill the minibar for $25 the first night, including $8 for a pint of rum and $3 each for the island’s national beers (light and crisp Cristal and the richer and darker Bucanero) before heading to the liquor store the next day at the former Havana Hilton—now the Habana Libre—to restock. There, your $8 buys you a bottle even huger, and the beers are a buck.

Others may sniff that the Hotel Nacional is not a four-star joint, but we do not live in such luxury at home, and it is something we could get used to fast. Our room is huge, situated right in the middle of the long, palm-lined drive and facing out onto the stunning cityscape of ’60s buildings that could be in Honolulu if they had a new coat of paint. As it is, they are peeling lavender and red and every conceivable shade of blue, and we can sit in the small rocking chairs by our big windows, drinking rum and watching the afternoon go by, or turn our heads in our big bed and see the colors of the buildings pop against the gray morning sky.

After a year unemployed, we’ve yet to struggle to pay our rent. We’ve yet to consider a manual job. And now we are here for a week on the executive floor of the Hotel Nacional, where we giggle at the dirt-cheapness of the contents of the minibar and offer ourselves as consultants to the Cuban government on the proper way to gouge a tourist. For me, budgeting has meant cutting out the organic in everything but my milk; it hasn’t meant no fruit at all. There is no question how rich we are.

One day, the whole group of us is bused out to the beach, for a day at one of Cuba’s all-inclusive resorts. But while it is nice to drink a beer, and have a ride on the (included) catamaran, we would have been just as happy at a regular beach without a resort on it and without a buffet lunch. I don’t know if it’s policy to keep us somewhere segregated, or if the travel company felt it was an excellent way to charge just a weensy bit more for our tour package, but really: even though we’re American, and even though half of us are Old, we would have been quite glad to rough it at a Caribbean beach even sans the amenities. We are not so rich we need to be protected from the vagaries of a day at the beach.

La Doctor Es In

The people are hungry here. There are severe food shortages. I do not understand why a tropical island would lack fruits and vegetables (a severe lack, even for las turistas ricas who can pay good money for it), and my only assumption is that maybe they have to export it all. Cooking is mostly tasteless, with no spice and certainly no produce. At the hotel, the extravagant breakfast includes canned pears and juiceless, dessicated pineapple and an odd stewed mango (I think). A vegetable salad ordered from one of the hotel’s many restaurants comprises only carrots and cabbage and a few slices of cucumber, with a tomato wedge for luxury. After a strenuous morning of walking and gawking and treating ourselves, Paul and I choose a restaurant on the outskirts of Vieja because it has a new paint job. Oh, and because it’s called “Hanoi.”

Before they strike up, we talk a long time with Ariel, the singer of the band Trio Ases del Tropico, about Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh, and how my mom wants to kiss Fidel on the mouth. His English is excellent, and his music’s better. Before we leave, he says we must stay for one more song, it is his special song for us, and he and his bandmates start on what will be our romantic song, “Hasta Siempre Comandante.” If Paul ever marries me, I swear to whatever God is in heaven above: I am walking down the aisle to a song about Comandante Che Guevara.

The restaurant is very inexpensive, and Paul orders seriously seven appetizers, he is so hungry for fruits and vegetables and potatoes—and I beg him not to, it’s too much food. Everyone in our group complains about the food all week, and it is certainly no frills or triple-crème brie, but I order a pina colada and it is fresh and delicious, and I order a rice dish with hard-to-come-by shrimp and chicken, and it is tasty too. But I am full already of potatoes and fruit slices, and I can eat only a few bites of my nice rice dish before leaving the rest. I am mortified to order so much and then leave so much on the table — it is our ugliest American moment.

We are rich, and we leave plates groaning with food, but back at la Hotel Nacional, I discover our friend Shervin has seen the hotel-doctor-on-call, and it was free but for tipping the nurses. I have something wrong with me! I would like to see the doctor too! We go down to her office and she looks at the ugly lump on my wrist and writes me a scrip for anti-inflammatories and some pain pills too (we do have to pay for the drugs themselves: $16). She looks askance at my question about whether we should slam the lump with a dictionary, which I have heard is the actual treatment, and tells me, “When you get back to your country, you should see your doctor.” I am too embarrassed to tell her I do not have a doctor back in my country. Doctors are for fancy people.

Not here, brother! But you knew that already. You knew that Cuba has the most doctors per capita on earth, and that they are constantly do-gooding all over the world — all despite the fact that there’s no money incentive for them. Every time some Ayn Rand blowhard says nobody will work unless we abolish the capital gains tax, I think of Cuban doctors, doing it for the challenge or the status or the urge to heal—whatever reason, but definitely not the paycheck.

I’m too embarrassed to tell the doctor I don’t have a doctor stateside not because I’ll look poor or something, but because it makes our country look ass-fucking-backward. In 2013, I will have a doctor. It is going to be awesome.

Lady and Dayam

And here is the shittiest thing we did. As we walk home through Centro one day, I already worrying that perhaps my smiles come off as some gross postcolonial Lady Bountiful gifting the peasants with her approbation—ah, how quaint and picturesque is your slum! I am delighted to see you in it!—I am stopped by a slight black boy, maybe 20 years old, who asks me “Espanola?” No, Americana, I assure him, and he switches to English and starts to talk. His mother has died, he says, which may or may not be the case, and he is caring for his sister. Can we help him out? We have no money left, we lie. What about some soaps or gifts for his sister? In fact, I have suitcases of just such things brought for the families of some people we were supposed to meet, as well as the hotel housekeepers. He is welcome to come by the next day and get some! I give him my card, so he can spell my name at the desk, and he asks for my room number and I give it. Paul, a few feet away, starts to have a small stroke, and we go on our way, with Dayam’s promise to see us tomorrow.

“He’s a jinetero!” Paul is worrying, a street hustler, and I have just given him all my info! And I start to feel so stupid, and so down, that I don’t even join the others for an evening’s carousing, but stay in and watch The Blind Side instead.

In the morning, we wait around until Dayam has called before joining a few others on the way to Vieja, and we tell them the story, and we’re a little bit scared. And there in the lobby is Dayam, and he has brought his sister Lady to meet us, and they are in their finest, most elegant clothes — a long-sleeved button-up with stylish embroidery for Dayam, and a really pretty sundress on Lady — for a visit to the regal Hotel Nacional. I hand a bag to Dayam, kiss him on the cheek, and we go off with our friends, without inviting them to join us. It wasn’t even the best stuff: no cosmetics, no lipsticks, not even a Commie Girl T-shirt—just some aspirin and razors and toothpaste and such. And our friends look at us and cackle: That was the boy you were scared of? That lovely young man who brought his sister to meet you? What were you afraid he was going to do with your card? Call you on the phone?

We spend the rest of the day hoping Dayam will call again, so we can take them for a drink or a meal or at least give them a better grab-bag, and he does, but by that time we’re in the wind, jet-setting with the Puerto Rican rock stars who are staying at our hotel, as is our wont, because we’re rich.

Sometimes, we really suck.

A Perfect Ambassador of American Goodwill

Whenever I’ve been lucky enough to travel, I’ve always attempted to be the perfect ambassador of American goodwill. In Golden, Canada, I made sure to leave the kitchenette in our sweet brookside cabin spotless after making a pot of (prefabricated) pesto, because I was representing for all my country. In Paris, I smiled endlessly, like a child with Down syndrome, and kept my loud American voice as low as I could. In Mexico, I always make sure to buy some crap jewelry I will never wear again from whichever man is carting his case around. In London, I tried, but even addressing a woman who was sitting at the same table with the same group of friends earned me only a confused, “Did we meet?”

Whatever, London .

In Havana, it is far more fraught than that. To the rest of the world we may be loud moron bullies, but in Cuba, we’ve been screwing them since the Spanish-American War, in which after 50 years of rebellions, Cubans finally earned their freedom from Spain only to have the U.S. step in and force them to add a cozy little addition to their constitution called the Platt amendment, allowing us for all time and forever to intervene at our will. Also, we occupied them a bunch. And tried to kill Castro a lot and incessantly, and embargoed and blockaded them, and other stuff too.

We’ve been harboring Luis Posada Carriles, for instance, since he downed a Cuban charter plane and killed all 73 people onboard. Two weeks ago, he marched in Miami with Gloria Estefan. The rhythm may have got him, but the authorities did not.

And so here I am above and beyond my usual nice-tourist shtick. I smile endlessly, all please-and-thank-you. I attempt to speak Spanish, even though I know only nouns and adjectives—no verbs, ever (except the ones in titles of Gipsy Kings songs), or pronouns, and certainly no prepositions. Paul’s Spanish is even worse than mine—despite spending all of his 49 years in Los Angeles, he sounds like he is from Wisconsin the few times he tries—and so I am our designated talker, and I say things like “Por favor, a la grande solar ... salon ... avec la ciudad la Habana?” and the nice police lady looks at me blankly for a while and consults with her nice policemen friends while I try again, this time making my hands into a square and saying, “Un grosse ... grande ... salon con la total ciudad la Habana inside it.” La Maquetta, they decide, the storefront with the big model of the city of Havana inside, and direct me to it with kindness. My Spanish is dotted with French and Italian—occasionally I tell people “grazie” and then immediately answer “prego” for them—but mostly it is German that keeps falling out of my mouth, and that is not helpful at all.

I’m trying to be a perfect ambassador of American goodwill, but I do not at all succeed. I get mad at the coco-taxi lady. Si si, amigos rapido, but even so, I’m pissed when she charges us $10 for what everyone knows is a $5 taxi ride, and then Paul tips her $3 on top, because he is embarrassed to ask her for change from his $3 bill. Tipping well and often doesn’t include when someone’s just ripped you off! She is not our amiga rapida! Es no bueno! I manage just barely to talk myself out of my snit.

Then there is the Dayam fiasco.

And at one point, we have gone to some lame club out in the richer suburbs of Playa or Miramar, we have no idea which, with a British national who’s here to do vague and sleazy-sounding “promotions” work in partnership with the government. (He sounds more like any of your prototypical buzzards trying to get in before the multinationals, but he’s certainly friendly and warm, including to the two Swedes who’ve joined us, and who may break up their friendship accordingly since apparently he took one home before setting his sights on the other.)

At the club, women get up from their tables to tap me on the shoulder twice in a matter of minutes and tell me to move because I’m blocking their view. We’re smashed by this point, of course, having had a few friends to our room to polish off a bottle of Havana Club rum (never drink it with Coke, because then you think you’re just drinking Coke!), and while we don’t understand exactly what it is they are trying to look at, I also am chastened and have a moment of drunken lucidity. I’ve stood on club floors and watched the band, without a soul within 20 feet, only to have men of six feet or more come and stand directly in front of me. I was pissed, but never asked them to move, and I should have. It is like the scene in The Last Emperor, when the Last Emperor is called into the manager’s office at the work camp or whatever and told he is urinating too loudly in the middle of the night and thus he is waking the others. He must urinate on the side of the bucket so it is quieter. I do not have any right to pee in the middle of the bucket! I do not have any right to block the view of others! And next time someone blocks mine, I will tell him so and make him move!

Then Paul falls on somebody, because really, we’re disgracefully drunk, and not the littlest bit repentant! We are Ugly Americans, and having just a marvelous time!

The next day, we go with some of our friends to the Callejon de Hammel, a little alley famous for its folkloric murals and its rumba show, and also for its pickpockets. I’m told to keep an eye on my purse, which rankles, but then the swarm of ninos malos starts grabbing out of my hand the chocolates I’m trying to give them while I’m saying “Momento! Momento!” and trying to hand one to the boy who’s been waiting patiently, but other children keep snatching it before I can, and a grown man sticks his hand in my purse not at all suavely — really, he needs to work on his skills, because I never should have seen it, and I did — and I’m fucking mad and hate those children and Paul and I have had enough, and let’s get out of here and go for a walk to the university!

Even so, a kid has tried to sell me his rap CD, and while at first I brushed it off, I almost immediately remember I’ve promised my little brother I’d find him some underground Cuban music, and here is Tito la Escuela promising me an album of Cuban rap, and he’s maybe 19 years old, and hell yeah I will buy your album! He signs it for me — paz y amor — and kisses me on the cheek before directing us to the university a five-minute walk away. There, an old man is stationed at the top of the steps to tell us we may not walk onto the beautiful campus—the campus where Castro got his start in politics among the armed political gangs (Really! Armed political gangs on campus!) — and I make sign language tears of sadness, and ask the man then for directions por favor a la Hotel Nacional, and he spells them out s-l-o-w-l-y for us en espanol, repeating them until he’s assured himself he’s seen understanding replace blankness in our eyes. He sincerely wishes us a bueno estancia, patting my shoulder, and promises we may come back manana. I think my pathetic Spanish brings out people’s protective feelings. Or it might be my shy, dumb smile.

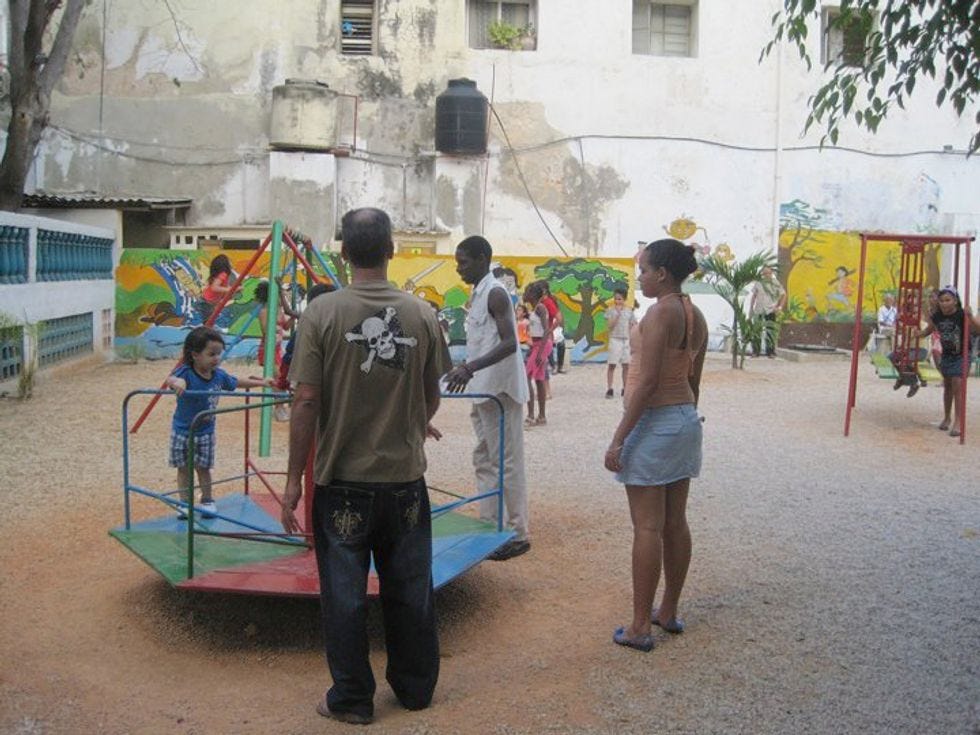

We want everyone to know how we love their nation — but we’re afraid to tell them, because maybe they don’t. One man in Centro shows off his Florida tattoo, talks about his brother in Miami, asks us how we like Havana and I attempt to formulate the sentence “Havana is the city of my heart.” He looks dumbfounded. How can we love it here? And I do not sneer, “Miami Cubans are bullshit!” about his brother. After a week here, like my mother we love Fidel. (But we do not want to kiss him on the mouth.) He has kept this island nation kind for its people with only the strength of his obstinacy—but if we say that too, then maybe we are the assholes who think poverty is fine and pure for others, as long as we ourselves are lord and lady of the manor. He has not been awesome at figuring out how many pairs of gold fuck-me-pumps people will need (nor was Che when he was minister of industry), and the blockade is only partly to blame for the want here—but there is a house for everyone, and a doctor down the street, and there are pocket parks everywhere for children to play (you’ve no idea how park-poor Los Angeles is until you’ve been somewhere that’s not), even if they’re roller-blading in an empty fountain. And the nation’s heroes are a writer and Che.

We love Fidel. We do. It is not “serious” to love him; it’s like Loving Saddam. But I am not sorry for the people whose extra houses he took — you still can own two, which seems plenty — and turned them over to the poor. I am not sorry for the landowners whose land he expropriated, turning it over to the sharecroppers. I am certainly not sorry for the Bacardi family, whose rum factory employed the most interested and engaged sons and sons-in-law while the rest of the family lived high on their dividend checks — even though they were a progressive family of Cuban patriots, immersing themselves in a hundred years’ worth of Revolution (including in Fidel’s — and with excellent labor relations to boot), until they exiled themselves and started getting all Bay of Pigs. That’s when they went a little loco — and decided they needed “democracy” by military coup.

It is not serious to love Fidel, and it also isn’t up to me to tell the Cubans what’s good for them. And so I keep my mouth shut and smile, and say only please and thank you. It’s not whether you succeed at being a perfect ambassador of American goodwill. Really, it’s that you tried.

This story originally appeared in 2010 in the sadly gone FourStory.org. All photos by Paul Takizawa .

Sounds like you are in good shape all around!

I liked dirt bikes when I was young too, but any kind of powered off-roading his hard to find in Germany. OTOH, mountain bikes are permitted on almost all trails, and they are almost as much fun as an enduro when you head downhill. Uphill, meh, find a gear and grind away, and keep thinking "this is good for me...."

I choose to go with adorably clueless. AWWW.