Sundays With The Christianists: Nathaniel Hawthorne Had A Co-Author. Was It Satan?

If it's Sunday, this must be Christianists! Time to get all literary again, as we learn how Nathaniel Hawthorne is personally responsible for destroying Christianity in America, at least according to homeschooling advocate and radio preacher Kevin Swanson and his intellectual e-book masterpiece Apostate: The Men Who Destroyed the Christian West. Swanson documents, in irrefutable detail, how pretty much everything we think of as "Western Culture" has actually been part of an assault on Christianity, from Thomas Aquinas to Disney. (OK, Disney isn't in the book. But Swanson does think Disney movies will make your kids become gay witches .)

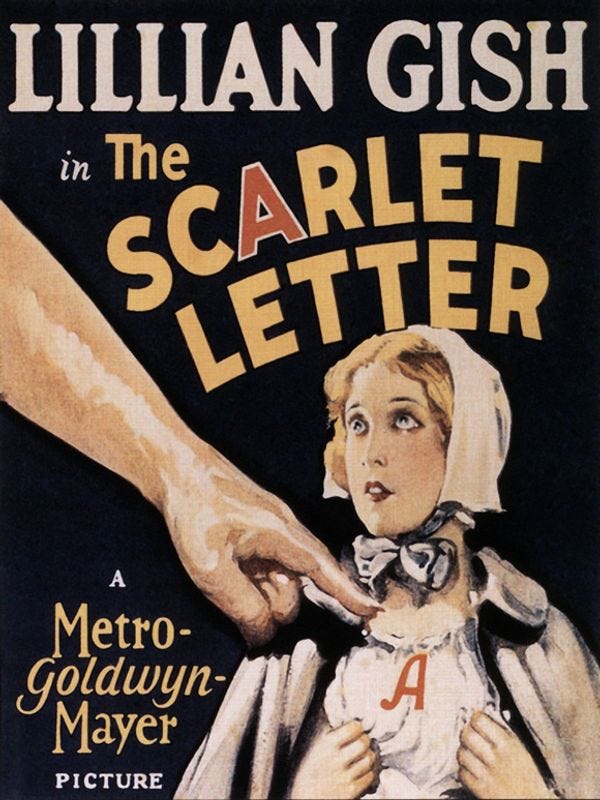

Before we jump into Swanson, Yr Doktor Zoom must share a little story about reading The Scarlet Letter in graduate school: I started out my grad school career as a literature major, and in an American Lit class, we read Hawthorne. By some odd curricular twist, I got through high school and an undergrad degree without ever reading The Scarlet Letter, although of course I knew what it was about. I may have been the only person in the class reading it for the first time. And so one day, when I saw Klaus, a classmate from Germany, in the library, I said, as if imparting a big spoiler, "You know what? I'm thinking that Hester and Dimmesdale had something going on, is what I think." He just looked at me blankly for a moment -- I'm pretty sure I'm imagining he sighed, but I can't guarantee he didn't -- and said, "Vell... I suppose you could read it for the plot." Take that, simple American narrative junkie! I switched my major to Rhetoric, Composition, and Teaching of English sometime after that.

Kevin Swanson certainly read The Scarlet Letter for the plot -- the plot against Christianity! (How's that for a transition?) He advises us that "no other single publication of any genre has been so effective at severing a nation from its Christian heritage," and explains that it

works psychologically; it penetrates deeply into the consciousness of millions of people, reshaping religious perspectives and humanist convictions concerning the Christian faith, the historical church, sexuality, guilt, judgment, atonement, and God’s law.

Well, heck, we guess he didn't just read it for the story, either.

Swanson really does not like this Nathaniel Hawthorne guy, mostly for his slanders upon the Puritans, who Swanson isn't entirely sure were fundamentalist enough for his own tastes, but at least weren't godless heathens like everyone else in America. Since the Puritans "represented a potent element vitally interested in retaining something of the Christian faith," then Hawthorne had to defame them in order to pursue his humanist agenda of overthrowing God. Swanson likes the Puritans a bunch, since they were "supremely orthodox, spiritually disciplined, and theologically balanced," and recommends that "any committed Christian" should read Puritan sermons and theological works rather than "accepting the word of an apostate" -- i.e., Hawthorne's portrayals of the sect.

We do hope you'll put down your coffee, lest you spoil your keyboard or monitor: We actually agree with Swanson on one thing here, and that's his assessment of Hawthorne's impact on how we think of the Puritans:

In spite of their cultural importance and godly influence in America, England, and Scotland, most of the “Christian” West either ignores the Puritans or despises them. Among professing Christians, most are either ignorant of this heritage, or they are embarrassed by it. This cultural disposition is largely a product of Hawthorne’s skewed characterizations of the Puritans. Throughout his books, they are presented as harsh, vindictive, and hypocritical killjoys.

Mind you, there's also plenty of evidence beyond Hawthorne -- like their own writings and actions -- to back the view of Puritans as "harsh, vindictive, and hypocritical killjoys," but we're happy to concede that Hawthorne did a bang-up job of fleshing out that portrait. And of course, we have to recommend a more recent look at the Puritans as well, Sarah Vowell's brilliant The Wordy Shipmates.

A good part of Hawthorne's antipathy to Puritanism was rooted in family history: his great-great-great grandfather, William Hathorne, was among the first settlers of New England, and was a magistrate under John Winthrop. Swanson has a good chuckle at just how totally wrong Hawthorne was to think his ancestor was some kind of extremist:

Nathaniel Hawthorne hated this man for his austere dealings with the Quakers, specifically for the whipping of a certain Quaker woman named Anne Coleman. While he attributed this civil action to William Hathorne, historical records indicate that the sentencing of Anne Coleman actually occurred under Richard Waldron, another magistrate, and Hathorne had nothing to do with it.

Stupid Hawthorne! Sure, your great3grand may have participated in a judicial system that whipped dissenters, but he never ordered that one lady whipped, so what is your big deal?

Swanson also treats us to a deliciously bizarre apology for the Salem witch trials, in exonerating another Hawthorne forbear, his great-great grandfather, John Hathorne, one of the judges in Salem -- and, in a detail you won't find in Swanson, the only one of the Salem judges who never repented of his involvement. Swanson is quite happy to handwave past John Hathorne's flaws as a supernatural investigator so that he can tell us once more just how wrong Nathaniel Hawthorne was about the whole thing. We've included Swanson's hilarious footnote, which indicates just how skewed Hawthorne's priorities were:

From historical records, it does seem that John Hathorne acted on flimsy, “spectral” evidence for his adjudication of certain cases.* Nevertheless, it is clear that Hawthorne was not interested in the details of these proceedings. It was the Puritan pastors who put an end to the trials on the basis of solid biblical reasons. But that wasn’t important to Hawthorne.

* We must allow that some of the Puritan magistrates were over-zealous in their civil duties and assigned civil punishments beyond that required by biblical law. Nevertheless, it is important to remember that the governments controlling our socialist nations today are far more intrusive into the lives of the average citizen than what we find in early colonial world.

Yeah, Hawthorne, why did you complain about the witch trials when we have the EPA and the IRS today, huh? In addition to failing to anticipate the Republican anti-big-government platform of 1980 to today, Hawthorne has an even greater problem:

At the root of it, Hawthorne’s real sin was his refusal to acknowledge the sin of witchcraft as a true violation of God’s law. As a humanist who thought and acted independently of the law of God, he would accuse the Puritan magistrates of injustice by his own arbitrary humanist “standard.”

Swanson circles back to the Salem trials later in the chapter, explaining that while, sure, the Salem magistrates went a little far, the problem wasn't that they were prosecuting witches, but that they didn't follow biblical rules of evidence:

Before the age of humanism, Christian countries opposed witchcraft and took biblical passages like Exodus 22: 18, 2 Kings 23: 24, and Deuteronomy 18: 10 seriously. These texts recommend extradition or the death penalty for witchcraft. In an older era, such laws did not seem overly stringent [...]

We still maintain that there were serious problems with the Salem “witch hunt” proceedings because Puritan pastors admitted this to be the case. According to Increase Mather and other witnesses at the Salem witch trials, the court admitted “spectral evidence,” or evidence based on dreams and visions instead of eyewitnesses. Biblical law requires two or three human witnesses (who themselves are not guilty of committing the same crime) to prove the innocence or guilt of the party. What Hawthorne refuses to mention is that it was the Puritan pastors who put an end to the witch trials at Salem. These are the very pastors he mocks in his stories.

Obviously, if the eyewitness testimony had just been a little stronger, nobody today would have a problem with the Salem trials. Why can't people just see this simple fact?

There is, in fact, so much deep weirdness in Swanson's chapter on Hawthorne that we are going to just close here, and continue next time with his critique of The Scarlet Letter -- plot and everything -- and Swanson's strong suspicion that the magistrates of Salem may have been right after all, because what if 17th-Century New England really was under demonic attack, huh?

Programming note: There's a William Burroughs holiday and some wedding going on next weekend and Yr Reverend Doktor Zoom will really try to prep Hawthorne Part II: Demonic Boogaloo in advance. But if not, blame the tryptophan. (Fine: blame the placebo effect .)

I fear I don't have that long.

Okay, that made me literally (sense one) chuckle.