Sundays With The Christianists: U.S. History Books That Begin Bombing In Five Minutes

Our Celebration of All Things Reagan continues this week with a look at some of the Gipper's flawless successes in foreign policy, as explained in a couple of popular history books for the private Christian school market. It was a time when America rode tall in the saddle again, and everyone loved and respected us again. And if they didn't, they'd get Rambo'd!

The main thing children need to know need to know about this glorious period in history is that Jimmy Carter's wimpy emphasis on "human rights" was replaced with manly firmness by the Reagan Doctrine, which our 8th grade textbook, America: Land I Love (A Beka, 2006), describes as Reagan's belief "in stopping Communism before it could attack and enslave a country." Our 11th/12th-grade text, United States History for Christian Schools (Bob Jones University Press, 2001), defines the doctrine a bit more accurately as a "policy theme" that "pledged America’s support to insurgent groups battling Communist governments in the Third World," although it leaves out the part of the Reagan Doctrine that also helped governments terrorize their own people in the name of anti-communism. You won't hear about El Salvador's death squads or the murders of nuns in either book.

Not surprisingly, the liberation of Grenada gets a prominent mention in both texts; by a miracle of editorial placement, neither mentions that it occurred two days after the suicide bombing of the Marine barracks in Beirut. Both events are in both books, but they don't need to be mentioned in proximity to each other, because Grenada falls under the heading "Central America" and "the fight against communism" while Beirut clearly belongs under "Middle East" and "the fight against terrorism." Easy-peasy, just like the invasion itself!* As usual, Land I Love is far more certain of the absolute geopolitical importance of the action:

In 1983, President Reagan learned that the Cuban dictator Fidel Castro planned to take over the island nation of Grenada in the West Indies and use it as a military base to invade the mainland of South America. Castro thought that the United States would be too cowardly to resist his plans to conquer Latin America.

Boy oh boy, was he ever wrong! Maybe that wuss Carter woulda given away Grenada like he did the Panama Canal, but not Ronald Reagan!

A small force of Cuban military men had already arrived in Grenada when the Grenadians and other Caribbean islands called on the United States for help. To prevent a full-fledged Communist invasion, President Reagan sent American troops to Grenada to defend the people. The Grenadians gratefully welcomed the American soldiers to their island. With the help of armed forces from neighboring islands, the Americans quickly rounded up the advance guard of Cubans and shipped them back to Cuba, saving Grenada and the continent of South America from a Communist invasion.

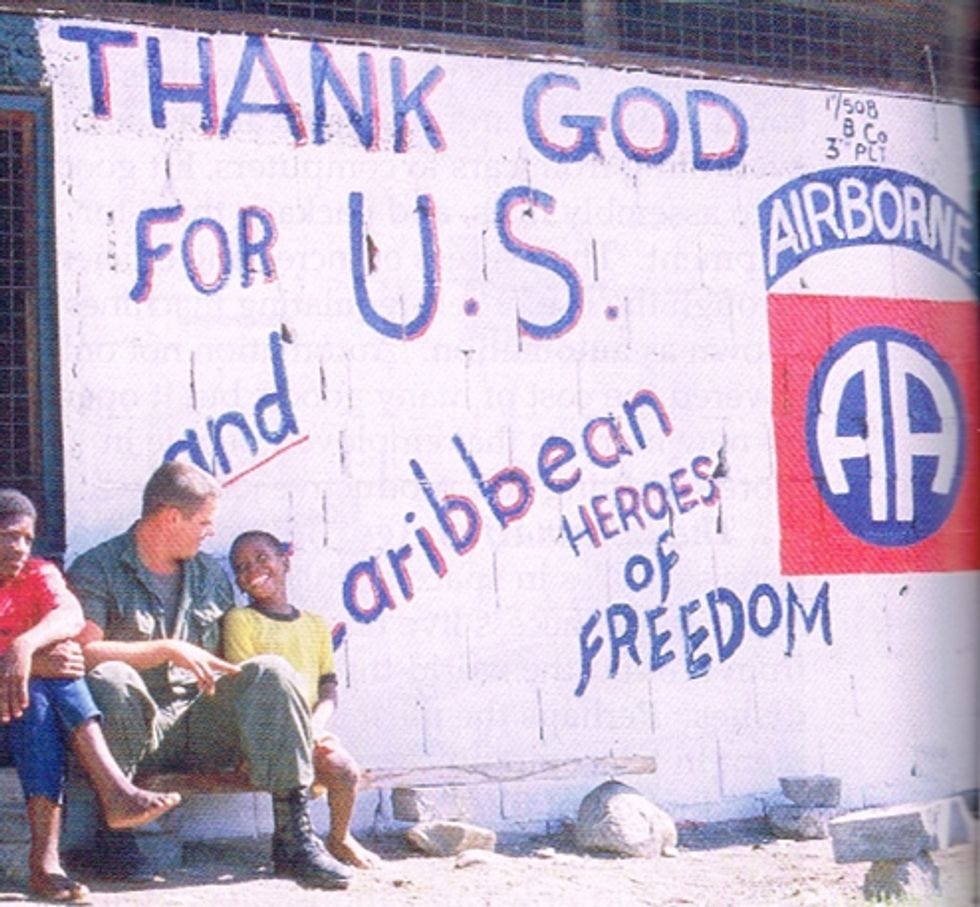

Just to make clear what a huge success Grenada was, the book includes this photo:

(Incidentally, a 2012 travel piece shows the above graffiti still in place, though considerably deteriorated.)

U.S. History is considerably less panicky about the prospect of Fidel Castro taking over all of South America:

Grenada, a tiny island in the Caribbean, was being transformed into a fueling station for Cuban troops sailing for Africa and Soviet advisors heading for Nicaragua. In October 1983 the Communist government of Grenada under Maurice Bishop was overthrown by a more radically Communist faction, led by General Hudson Austin. Bishop was murdered, and calls to the United States for help came quickly from neighboring islands. Armed with this appeal, concerned over the safety of a number of American medical students living on Grenada, and fearful of a second Cuba in the Caribbean, President Reagan ordered nearly 2,000 U.S. Marines and airborne troops to liberate the island. Although a relatively small military operation, Grenada had huge symbolic importance. It sent a clear signal of American resolve to Communist leaders and ended much of the post-Vietnam fears and frettings over the use of American military force.

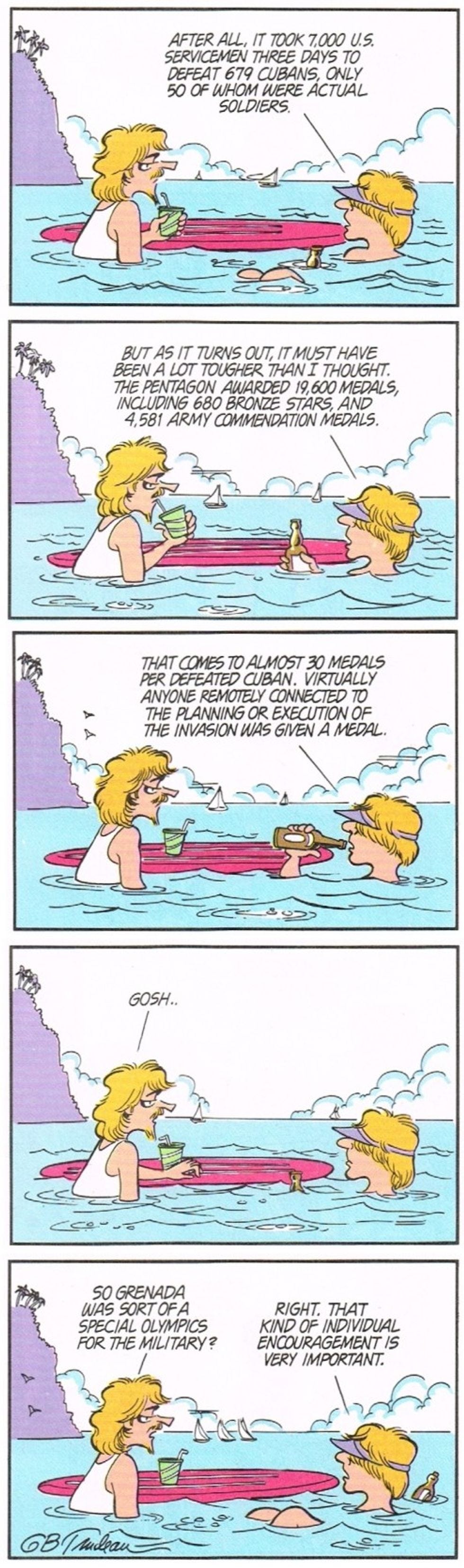

Needless to say, neither book mentions the Bizarro-world aspects of Operation Urgent Fury -- the communications failures when Army, Navy, and Marine units found their radios were on different frequencies, the tourist maps (with gridlines helpfully added, and the new airfield drawn in by hand) given to soldiers, or the poor intelligence: when the rescuers arrived at the medical school to liberate American students -- ostensibly a key reason for the invasion -- that was the first time they learned that a lot of the students were at a second campus that the invaders had never been briefed on. No mention, either, of all those medals that were given out, far more than the number of actual combatants, which prompted one of our favorite Doonesbury strips of all time, excerpted below:

American involvement in Central America is similarly tidy in these books, and is of course an uncomplicated matter of opposing international communism. Consider El Salvador, where the government assassinated Archbishop Oscar Romero and four American nuns -- albeit before Reagan took office -- and where massacres by the Salvadoran army were a regular occurrence, resulting in some 75,000 people being killed or "disappeared." Here's everything Land I Love has to say about El Salvador:

The Soviets and Cubans continued to stir up rebellion and bloodshed in Central America during the 1980s. In addition to large amounts of military and economic aid, President Reagan sent 50 military advisers to the Central American nation of El Salvador to prevent a Communist takeover there.

Similarly, U.S. History takes the long-distance perspective, so you can't see the bloodstains:

Early in 1981 fighting between Communist rebels and the democratic government of El Salvador flared in the tiny Central American republic. Reagan responded to the aggression of the Soviet and Cuban-backed guerrillas by supplying arms, military advisors, and economic aid to the beleaguered Salvadoran government under President José Napoleon Duarte.

Why mention a few murders of Catholics, anyway? Or the El Mozote massacre? Or the School of the Americas? Only Birkenstock-wearing hippies care about that stuff, which is ancient history. We stopped Communism!

American support for the Contras in Nicaragua also gets a mention in both books; weirdly, Land I Love discusses those "moral equivalents of the Founding Fathers" (a phrase that also isn't mentioned in either book) only in its section on the Iran Contra scandal (more about which in another outing). You'd think those brave warriors would get more attention for their own sake. U.S. History gives the Contras a couple paragraphs, and even notes that the rebels were organized by the CIA. The text acknowledges that Reagan's support for the Contras "ignited fierce debates in Congress" (though apparently nowhere else in the entire country), but attributes that controversy solely to critics' claims that

reviving "big-stick" policies would renew anti-Americanism throughout the region. They urged compromise with the Sandinistas and increased economic aid to the region. Reagan, however, believed that the Sandinistas posed a threat not only to the democratic elements within Nicaragua but also to the security of all of Central America. With the Soviets supporting Nicaragua’s Communist government, particularly through its satellite state of Cuba, support of the Contras also represented a vital test of American commitment to the Monroe Doctrine.

Not mentioned in there, of course, was the Contras' record of human rights violations, because duh, we told you that was Jimmy Carter's thing, and Ronald Reagan dismantled that foreign policy emphasis around the same time he took the solar water heating system off the roof of the White House.

There is a whole lot more to be said about Reagan and foreign policy -- and we will say it next week, because there's only so much ranting one should do on any given Sunday.

*Update/clarification: As commenter Steverino notes:

Grenada was in the works before the Lebanon bombing, probably as soon as the coup of October 16. Nothing that big gets done that fast. The decision to actually go and when certainly could have been affected by the bombing, but all that stuff doesn't move that fast, especially the Navy which is limited to about 20 knots per hour. I despise Reagan for a lot of reasons, but saying he was able to execute a plan and move all those military assets in two days is as much a fantasy as Benghazi stand-downs.

And Yr. Doktor Zoom agrees -- didn't mean to suggest that the Grenada operation materialized out of thin air after Beirut; rather, we'd say that the bombing made the decision to invade far easier, and may have also pushed up its timing. It might have happened anyway, but it was definitely a terrific distraction from Beirut.

Follow Doktor Zoom on Twitter. He regrets any typos in this piece. Mistakes were made.

Not really . . . it's just that the elbows aren't where you think they are.

Still a buck at most NYC street carts, too. Of course, it's still the same stuff that passed for "coffee" in the 1960s, which is why Starbucks does well here.