Sundays With The Christianists: American History Textbooks For Homeschoolers Whose Father Knows Best

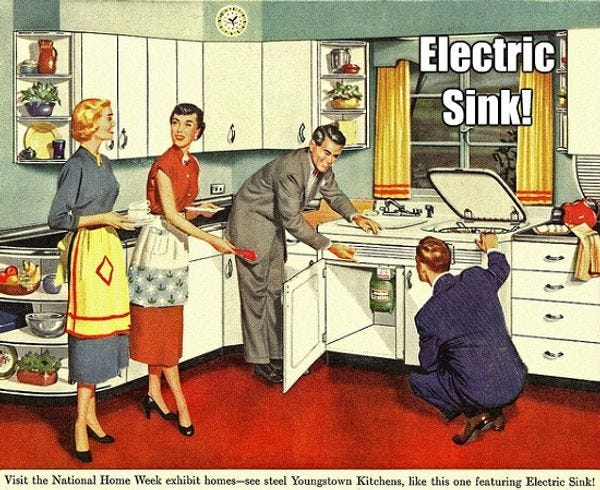

Let's all hop into the Chrono-Tron for a dynamic trip to the Populuxe world of the 1950s, courtesy of a couple of rightwing Christian textbooks for the homeschool market. Along the way, we'll learn that small government and pious people of faith created prosperity, and the decade's high tax rates on the wealthy never have to be mentioned because that would be really inconvenient.

Our 8th-grade textbook America: Land I Love (A Beka, 2006) is pretty sure that the economic boom of the '50s had little to do with anything the government did; rather, the bestest thing about the '50s is that it was a time when "the moral values of Biblical Christianity provided a just standard of law, order, and mutual respect, which in turn increased material prosperity." The book's chapter on the '50s leads off with a section on "Moral Strength," and subsections attribute the decade's good times to "Respect for Christianity," "Strong families, little crime," and to the "Sanctity of life" -- just in case students need three main paragraphs for their 5-paragraph essays. We learn that even though church attendance was, sadly, not universal,

most people respected the Biblical teachings of law, order, and moral decency. Local governments often required stores to close on Sundays, and community activities were planned in many areas not to interfere with church services. School days often began with prayer and Bible reading, and parent—teacher meetings and civic organizations usually opened with prayer.

In other words, it was as close to paradise as America got in the 20th century.

As an example of this increased piety, Land I Love approvingly presents the enormous popularity of Billy Graham in the '50s, a development that our 11/12th-grade textbook, United States History for Christian Schools (Bob Jones University Press, 2001), is considerably less impressed with, largely because Bob Jones University has never liked that Graham fellow on doctrinal grounds. U.S. History is careful to point out that Graham

became the center of the major postwar dispute in fundamentalist Christianity. In 1957 Graham accepted the sponsorship of liberal Protestants in a New York City crusade. To Graham and his supporters, such a move would help bring fundamentalism into the mainstream of public life and allow it to build bridges to liberal Christianity. However, many fundamentalists broke with Graham over the issue. Having come through the fierce struggles with modernism in the 1920s, these militant fundamentalist Christians would not compromise their faith by joining with unbelieving liberals.

Also, U.S. History tut-tuts over the ecumenical movement, which it sees as a well-intentioned but corrosive influence, with organizations like the National Council of Churches "uniting dissimilar bodies in cooperative organizations, sort of religious versions of the UN." It was a nice idea, but ultimately dangerous, because it

compromised the truths of Scripture in order to achieve outward unity. Significant differences in doctrine and even modernistic unbelief were all tolerated in the interests of unity. Proponents of the movement did not seem to realize that true Christian unity involves spiritual unity built on God’s truth.

Which is to say, ecumenicism would have been OK if only all Christians had the good sense to be fundamentalists. We love seeing a good Jesus Fight!

Another great thing about the 1950s is that families were strong and there were no teen pregnancies even though neither book addresses the untidy fact that, out here in reality-land, teen pregnancy rates were higher in the '50s than today. But it only happened to bad girls who got married or sent away. Even better, divorce was rare, especially since Land I Love conveniently sweeps aside the post-WWII spike in the divorce rate, as hasty pre-deployment marriages collapsed after soldiers returned home. U.S. History at least acknowledges the increase in the divorce rate starting in 1946, but doesn't suggest that disillusionment had anything to do with it -- it doesn't mention any causes at all. Probably moral laxity. In any case, families were Baby Booming everywhere, and according to Land I Love, it was a pretty idyllic time:

Most couples considered divorce a tragedy and made every effort to stay together and work through their difficulties. In small towns, people could leave their houses and cars unlocked. Children played in local parks without fear; in the larger cities, crime was primarily restricted to the back alleys. People considered the occult, illegal drugs, pornography homosexuality and other immorality to be disgraceful sins. Gambling was illegal in most places.

U.S. History admits that not everything in The Family was perfect, however, because of concerns over juvenile delinquency, which some attributed to "television, movies, and crime comic books" (neither book devotes any attention to the delicious weirdness of the decade's Great Comics Panic, sadly). But the more likely culprit, U.S. History suggests, was that pointy-eared green-blooded communist Benjamin Spock, whose 1946 Baby and Child Care

may have contributed to underlying permissiveness, according to his conservative critics, by advocating less structured methods of child-rearing. Spock, popularizing theories of psychologist Sigmund Freud and philosopher John Dewey, wanted children eventually to become well-adjusted, guilt-free adults. His child-care book sold 23 million copies between 1946 and 1976. Only the Bible, a much better answer to the problem of human guilt, outsold it during that same period.

Ooh, Spock, YA BURNT!

But what really made the '50s such a great time, according to Land I Love, is that law and order prevailed because Americans respected the sanctity of life by executing evildoers:

Courts punished criminal offenders; people knew that if they broke the law, severe penalties would follow. Because people believed in the sanctity of human life, most states practiced capital punishment (the execution of those guilty of murder). Most people believed that God instituted capital punishment (Gen. 9: 5, 6) to discourage murder and to teach mankind the value of human life. Abortion (the killing of babies before birth) was illegal throughout the United States.

No, we cannot make up anything to top that. (For more on this weird perspective, see A Beka's World History book, also, too.)

As for the economic prosperity of the 1950s, U.S. History is pretty honest in attributing much of the postwar boom to "defense spending, a necessary expense given the challenges of the cold war, especially in Korea," so although there was a lot of tax money being thrown at missiles and airplanes, it was totally worth it. U.S. History also has some qualms about the decade's "unrestrained buying spree" by American consumers, fretting about the moral looseness of easy credit, high-powered marketing, and planned obsolescence. And like so many people who have only read the titles of famous books, the text cites John Kenneth Galbraith's The Affluent Society as a pretty accurate label for the prosperity of the 1950s -- completely ignoring Galbraith's deliberate irony, since the book was a critique of the era's disparities between personal wealth and that "public good" stuff that liberals like to natter on about.

For laughs, Land I Love attributes the nation's postwar prosperity to the drive and initiative of American free enterprise, without noting, of course, that the marginal tax rate on the highest incomes was 90%, which helped to boost a lot of that prosperity for the middle class. The textbook attributes the postwar housing boom to the GI Bill, for instance, but doesn't decry it as "government interference in the market." Similarly, another section, headed "Free enterprise for a strong America," states without a shred of irony,

Under President Eisenhower, free enterprise (capitalism) thrived. In 1956, the Federal Highway Act provided funds for interstate highways. Soon road crews were constructing great roadways, linking the states with anInterstate Highway System.Many Americans took to the new highways and toured the country in the late 1950s.

Other examples of "free enterprise" in this section include the completion of the Saint Lawrence Seaway and the initiation of the Space Race -- the establishment of NASA at least merits this mention of Big Government spending:

Private research and tax revenue generated by healthy private businesses enabled President Eisenhower to bring the United States into the Space Age.

Once again, this slips through with no condemnation of how bad that had to have been, because the government was picking winners and losers in the aerospace industry. Needless to say, federal aid to schools for math and science education in the panic over Sputnik also gets no mention in either book, not even as an ominous precursor to a "federal takeover of education." And Eisenhower's warning about the power and influence of the military-industrial complex somehow goes without mention, possibly due to lack of space.

Hey, how about 1950s culture? Both books mention television, of course, emphasizing the popularity of family fare (and not saying too much about the late-decade popularity of more violent stuff like The Untouchables, because the '50s were a happy time, remember? U.S. History rather astutely discusses the popularity of rock 'n roll in a paragraph on marketing and technology, noting that businessmen quickly exploited its popularity by selling transistor radios, record players, and teen culture in the form of magazines and movies -- but it makes sure to sadly shake its head and add that many teen idols "symbolized rebellion against traditional values." Surprisingly, the moral scolds who wrote Land I Love make no mention at all of the rise of rock in this chapter, although they do finally get to a sound condemnation of its pernicious influence in their section on the 1960s. Perhaps they were worried that kids might not find Elvis scary enough, so they saved any critique of rock for a decade when they could gripe about the Beatles coming under the influence of scary dope gurus.

Next Week: Those Fabulous '60s! Atheists, hippies, and rebellion, oh my!

Frank Luntz probably uses the term "Contrarianism" or "Common Sense" instead.

Whereas I have too much irony in my diet.