Sundays With The Christianists: American History Books That Expose FDR's Socialist Agenda

Last week, we learned that the Great Depression was caused by government regulation of free enterprise, and that while it was a tad uncomfortable for some, there was no need for any government interference in the wonderful job that private charities were doing to help people. Or at least, that's how the Great Depression unfolds in the pages of our eighth-grade textbook from A Beka, America: Land I Love. This week, we'll once again make only occasional mention of our other textbook, the 11th/12th-grade United States History for Christian Schools (Bob Jones University Press, 2001), because while it's got a definite conservative slant, it at least resembles reality.

Land I Love, on the other hand, stops just short of saying Franklin Roosevelt was a commie, and certainly reminds kids at every turn that the New Deal should be seen as "a big step into socialism" and that FDR's policies were unnecessary interference in an economy that wasn't really all that bad anyway. Now that grandparents who lived through the Depression are no longer around to pollute the kids' awareness with any firsthand accounts, it's relatively easy to feed them a straight diet of rightwing revisionist bullshit.

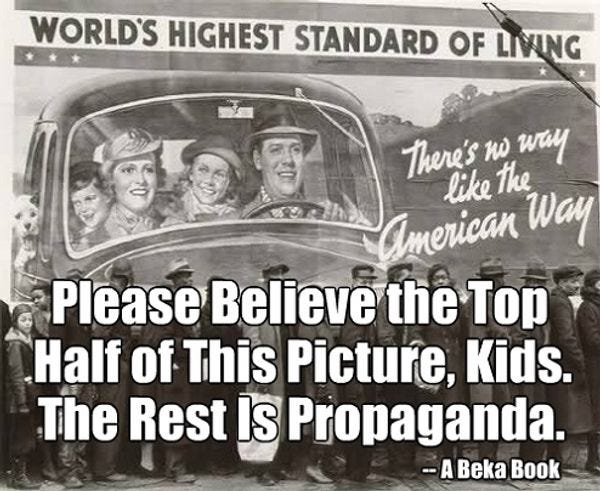

As we noted last week, Land I Love insists that most of what we think we know about the Great Depression was exaggerated by those who "wanted to create an imaginary crisis in order to move the country toward socialism." John Steinbeck exaggerated the difficulties of migrant farm workers, and photographers like Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange (not actually named, of course) presented photos of poor mountain folk who just plain never cared for modern conveniences, and presented them as if living in a one-room shack was a step down from their normal lifestyle. Similarly, Land I Love asserts, other troublemakers fibbed about the extent of the financial crisis:

They spread rumors of bank mortgage foreclosures and mass evictions from farms, homes, and apartments. But local banks did all in their power to keep their present tenants. The number of people out of work in the 1930s averaged about 15 percent of the work force; thus 85 percent continued to work. Most had to take a pay cut, but prices also declined during the Depression, enabling people to buy more for their money.

We also learn that virtually all critics of the glories of unfettered capitalism were dupes of International Communism, because no sane person could possibly think that factories ever treated their workers unfairly:

In some cities, Communist sympathizers stirred up trouble between factory owners and workers, encouraged street violence, and called for the overthrow of the government. Some labor union organizers demanded violent change, but most wanted to elect liberal politicians who would regulate the private business sector. In the end, the workers suffered most from the strikes and labor violence. Some writers and intellectuals used the Great Depression to criticize the American free enterprise system, but most Americans condemned their radical talk.

Everything's fine, really. The textbook balances a photo of children standing in line to get free milk from the Salvation Army with another photo of a family sitting at a well-provisioned table; the second caption reads "Despite hardships in the Depression, most families were able to provide for themselves."

From a spiritual perspective, we learn that "Churches grew as Christians and non-Christians looked to God in their hard times." While some Modernist denominations continued to accept lies about Darwinism, for the most part, "Fundamental, Bible-believing churches" thrived, and accomplished all sorts of impressive abstract gains:

Their influence continued to affect the character of America, producing morality, honesty, truthfulness, decency, and goodness. Other countries considered America to be a Christian nation because God was honored in public life and public places.

Unfortunately, not all Americans had the wisdom to see how well the country was weathering the Depression, because some had (egad!) a political agenda:

Most Americans worked hard, maintained strong family ties, and trusted God in their time of difficulty, but certain leaders began to convince people that the government should solve their financial problems. Some American writers and politicians saw the Marxist-socialism of Russia as a way out of the Depression. Why not let government do for the American people what it was doing in Russia and other areas of the world? As government interfered with the American economy, many people began to depend on it for their financial needs.

And so we finally get to Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who managed to win the 1932 election somehow. It's really unfair that Herbert Hoover wasn't more widely appreciated; after all, the poor guy "had taken office only 7 months before the stock market crash, but Democrats blamed the Republicans for the Depression." Again, no way did the speculative bubble and market crash have anything to do with the wise anything-goes policies of the Coolidge administration. Worse, FDR took advantage of people's discontents:

Because the Great Depression of the 1930s created hardships, many people were willing to accept socialistic ideas of government control and economic planning.

FDR also was an advocate of Demon Rum, and "appealed to the liquor sellers -- the breweries and bars -- promising to repeal Prohibition."

We then get a largely factual recitation of the "First Hundred Days," with the bank holiday and the Fireside chats: the textbook intersperses brief overviews of what the various New deal programs were with constant reminders that they were all about Big Government, which spent taxpayer money and interfered with private enterprise. Pay attention, this stuff will be on the test:

FDR believed that the government could spend its way out of the Depression by providing public relief and jobs for everyone. Roosevelt based his New Deal on the ideas of a socialist economist from Great Britain,John Maynard Keynes.The idea that government can live beyond its means is called Keynesian economics, the creed of "tax and spend" politicians. Under FDR the government began to operate on adeficit(spending more than received from taxes and other revenues).

And then Roosevelt took us off the Gold Standard, which meant that money didn't mean anything real anymore. We were a bit surprised that the editors managed not to identify that as the direct result of demonic influence.

And this is where we do need to throw in our one example of Massive WTF from our other textbook, U.S. History. In a section on Depression-era politicians who were more radical than FDR (Huey Long and his "every man a king" rhetoric, for instance), U.S. History has this to say about the infamous radio sermons of Father Charles Coughlin:

Coughlin turned his weekly radio program of religious sermons into a national political broadcast. By 1934 the eloquent Father Coughlin was telling his huge radio audience that the nation needed to abandon the "pagan god of gold" and coin large amounts of silver (thereby inflating the money supply). He also began to propose that capitalism be replaced with his own system of "social justice" ... [Coughlin eventually lost support] as the radio priest became increasingly violent in his verbal attacks against President Roosevelt and began to praise fascism.

That bit about praising fascism is the closest the passage gets to mentioning Coughlin's violent anti-Semitism, which seems like something a textbook should mention about the guy, no? On the other hand, by bringing up figures like Coughlin and Long, U.S. History is able to take a somewhat "moderate" stance, at least in comparison to Land I Love:

Although this radical opposition to the New Deal was ultimately unsuccessful, the wide popularity evoked by these socialistic schemes certainly posed a threat to America’s economic foundations. The New Deal, in comparison, was definitely the lesser of the evils.

We won't attempt to go over every single criticism of the New Deal in Land I Love; most of it follows the pattern of this section on the Tennessee Valley Authority: First, the textbook provides some nuggets of fact that can be spat out on a multiple-choice test. Then, it downplays the seriousness of the problem the program addressed, and then explains why the solution was terrible. The TVA, for instance, is accurately described as a program to "control flooding, conserve soil, and bring hydroelectric power to the mid-South." The editors even acknowledge that the construction created "many government jobs," though perhaps the fact that they were jobs with the government makes them bad all in itself. Then, we learn that the whole scheme was based on a lie!

An imaginary crisis. To generate public support for the TVA, promoters of the New Deal circulated pictures of soil erosion in parts of the South that were not even in the Tennessee Valley, including Ducktown, Tennessee, a copper mining area in the Appalachian Mountains. At Ducktown, acid from the mines left hillsides bare of trees, creating severe erosion. These misleading pictures led people to think that unless the government built dams in the Tennessee Valley, all of the soil would be washed away.

In many ways, Land I Love reminds us of Ronald Reagan and his legendary box of index cards -- here's this one factoid from Reader's Digest that somehow proves that an entire program was fraudulent. Was there any actual erosion in the Tennessee Valley? Did building the dams stimulate the economy? Doesn't matter -- some pamphlets used misleading photos, so the whole project is suspect. (And once again, what the hell is it with rightwingers and ducks?) Mind you, even though the TVA does seem to have accomplished something, that accomplishment is actually a form of enslavement:

Government control. The TVA dams generated electric power, which the government sold cheaply to surrounding communities. Thus, the government controlled the electrical power supply for millions of people.

And so on. The Works Progress Administration provided jobs, which most Americans approved of, because "unlike today’s welfare programs, the WPA insisted that people work before they received government money." But even though they built a lot of roads and stuff, lots of WPA workers were lazy, and "it was said that one crew would dig a ditch and another would come along and fill it in." And this had to be true, because "it was said" -- and we should note that this book was published before Fox News came into being.

Similarly, kids learn that Social Security started as "a voluntary program," but soon grew out of control:

The Social Security Administration soon blossomed into an enormous agency and began to transfer vast amounts of money to welfare programs. As more people were needed to contribute more money to keep the system afloat, Social Security became mandatory for most workers. Instead of saving the Social Security money for its original purpose, the government used the fund to pay for public welfare programs.

In the chapter summary, we learn that the New Deal was largely a failure, that it "prolonged the Depression," and that its main legacy was that "FDR’s programs marked the beginning of government interference in many aspects of the economy and people’s everyday lives." Fortunately, however, the textbook tells us that all that wasteful government control of the economy was nearly at an end, because

World War II would force the government to turn, once again, to individual initiative and private business. Only the American free enterprise system could produce the goods necessary to sustain and defend our great nation during time of war.

We can hardly wait to learn how the American war effort was financed without deficit spending or taxes. Presumably, America won the war due to free enterprise, because troops relied on their individual initiative and private financing, raising capital to arm themselves with the very best rifles, machine guns, bombers, fighters, aircraft carriers, and submarines that they could purchase on the open market. Heaven knows the industrial ramp-up of WWII and the prosperity of the 1950s had nothing to do with the socialist evils of Keynesian economics.

Next Week: Why We Fight: A reader shares how 12 years in a fundamentalist school left her largely unready for college.

Follow Doktor Zoom on Twitter. He promises never to control your supply of electricity.

I do take credit for their anti-intellectualism.

Upbringing and education sounds suspiciously elitist to me, but I am of course just a pointy-headed librulz.