Sundays With The Christianists: Smallpox-Infested American History Textbooks For Your Homeschooled Savages

Hey, history buffs, or historians in the buff as the case may be. After a brief detour into the novelistic sludge of America's Greatest Artist, we're back to our American History textbooks for the Christian school and homeschooling market. This week, once again, we've got a real contrast: someone seems to have let a real historian write the section on westward expansion in our 11th/12th-grade text from Bob Jones University Press, United States History for Christian Schools. For starters, it acknowledges that the "story of the American West" was not simply one of

courageous settlers overcoming the obstacles they faced in order to build a new and better land. Unfortunately, there is a darker side to the story. As white men moved west, they clashed with the Indians, just as they had done since the days of the Jamestown colony in Virginia.

It's pretty much the equal of what you'd find in a secular textbook, with no attempt to whitewash the murderous realities, and a decided lack of oversimplifying. Great for kids reading this textbook, but sadly, pretty much nothing for us to mock here. Happily for our purposes, our other textbook, A Beka's 8th-grade-level America: Land I Love, steamrolls over all the ickiness of the Indian Wars in a short section ingeniously headed "Problems of the Plains Indians." You might get more accurate history from a random episode of F-Troop.

For instance, take the buffalo, please. Here's what Land I Love says about the disappearance of the bison herds from the American Plains:

the great herds of bison began to disappear because of (l) settlement, (2) wasteful shooting, and (3) competition for grasslands with the large herds of beef cattle and, later, sheep. Soon the Plains Indians, who were hunters and not farmers, began to suffer food shortages.

Say, who did all that "wasteful shooting"? Never mind. Mistakes were made. U.S. History, on the other hand, provides a paragraph detailing just how central the bison was to the Plains tribes, and clarifies who pulled the triggers:

Buffalo were so important to the Indians that during the Indian Wars the U.S. government quietly encouraged slaughtering the herds in order to rob the Indians of their means of livelihood. By 1900 the huge herds of the Great Plains had become nearly extinct. Some historians believe that the destruction of the buffalo was more important in the conquest of the Plains Indians than any military campaign.

And where U.S. History discusses the unreliable treaties and untrustworthy land deals the government imposed, Land I Love gives us this:

Although the government paid them for their lands with a yearly allotment of money, the Indians lost much of this money to greedy liquor sellers who encouraged drunkenness. Tribal warfare and malnutrition plagued many tribes. Those Indian tribes who took up farming, however, began to prosper.

Oh, except for the ones who were herded onto land that couldn't be farmed. Pretty poor choice on their part, huh? Land I Love does briefly mention that the Sioux in South Dakota's Black Hills "had been promised that no white man would set foot in them," but that this promise didn't hold up so well when "in 1874, gold was discovered in the Black Hills, and prospectors began to swarm into the area." But darn it, the Sioux's pagan beliefs that the Black Hills were "'sacred ground,' the 'dwelling place of the earth spirits' which the Indians worshiped" just led them to do terrible things:

A medicine man namedSitting Bullof the Teton Sioux tribe claimed that the "Great Spirit" had spoken to him, warning that the white man was hurting the sacred Black Hills. If the Indians did not stop the white man, the earth spirits would be angry and the Indian people would die.

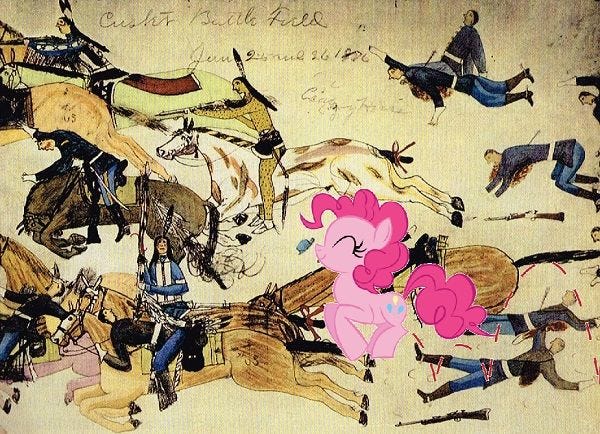

Soon, Sioux warriors began to attack and kill white settlers in the Black Hills and other parts of the Dakota Territory and Montana. In the summer of 1876, several thousand Indians led by ChiefCrazy HorseattackedGeneral George Armstrong Custerand 264 cavalry troops (soldiers on horses) at the Little Bighorn River (Montana) and killed every man, including Custer. Such incidents caused much hatred against the Indians.

Oh, did Crazy Horse attack Custer? Did he really?

Again, we can find some sanity in U.S. History, which notes that the U.S. Army often

demonstrated a remarkable ability to underestimate its opponents. For example, during the "First Sioux War" in the Wyoming-Montana region (1866-1868), Captain William Fetterman bragged that with eighty men, he could ride through the entire Sioux nation. Ironically, Fetterman had exactly eighty men with him when he met a large Sioux war party near Fort Phil Kearny, and he and his troops were slaughtered to the last man.

Rather than a single (inaccurate) sentence, U.S. History devotes almost a full page to Little Bighorn, noting that prior to that battle, "Under Crazy Horse’s leadership, the Sioux warriors fought one of the most unified, best-organized Indian campaigns in history," emphasizing Custer's habit of plunging into battle without reconnaissance, and explaining that despite the overwhelming victory by the Sioux, the battle

actually worked to the advantage of the U.S. Army. Thinking that the war was won, many Sioux left Sitting Bull’s force. Shocked and sobered by the defeat, the government quickly sent more men and supplies west to defeat the Sioux.

Nuanced history from Bob Jones University Press. Kind of wish they'd managed that for the Civil War, huh?

And then of course, there's Wounded Knee. U.S. History emphasizes the bloody awfulness of it, noting that it was a mindless slaughter, with "25 soldiers and over 150 Indians (half of them women and children)" killed. In the crazyland of Land I Love, the massacre is transmuted into the "last great Indian battle fought in the West," and was a direct result of Indians' delusional belief that the Ghost Dance would render them impervious to bullets:

The Ghost Dance led to a confrontation between U.S. soldiers and the Sioux on December 29, 1890, at Wounded Knee, South Dakota. Some 200 Indians, including women and children, died in the battle.

Where U.S. History closes its section on the Indian Wars with -- hope you're sitting down -- a discussion of Helen Hunt Jackson's 1881 exposé A Century of Dishonor (did no one at Bob Jones U notice that this book badmouths America?), Land I Love assures us that everything got better -- the Dawes Act of 1887 fixed everything, because it "offered land and U.S. citizenship to any head of an Indian family who would take up farming or ranching." Oh sure, the transition was difficult for some tribes who thought that it was possible to remain nomads, but eventually everything worked out just fine:

Today, many Indian tribes are working to improve life on their lands in the West. For example, both the Navajo and the Sioux have worked to develop ranching, farming, and industry. Missionary efforts continue on many Indian reservations.

And they all lived prosperously ever after, and many even found Jebus, THE END. Hey, let's go have a war in Cuba and the Philippines!

Next Week: Imperialism, the Spanish-American War, and other hijinks!

[Painting: "Battle of the Little Big Horn" by Amos Bad Heart Bull ]

By the way, this CBC documentary is excellent: <a href="http://www.cbc.ca/andthewin..." target="_blank">" rel="nofollow noopener" title="http://www.cbc.ca/andthewinneris/2013/09/19/trail...">http://www.cbc.ca/andthewin...

In Canada, during WWI, the group with the highest percentage of voluntary enlistment in the army was the First Nations. This after being royally screwed over. The Legion with the largest membership is on the Kahnesetake Mohawk Reserve outside Montreal.