Sundays With The Christianists: American History Textbooks For Homeschoolers In A House Divided

Break out the daguerreotypes and crank up the "Ashokan Farewell" (yes, we know it's from 1982), because it's time for some more Civil War in our Christian homeschooling textbooks. First off, a correction: Last week, we said that our 8th-grade text from A Beka, America: Land I Love, didn't say anything about the causes of the Civil War. This is inaccurate! We simply missed the entire third of a page it devotes to the topic, because it comes at the end of the section, just before it jumps into Reconstruction. And where our other textbook, the 11th/12-grade United States History for Christian Schools (Bob Jones University Press), identified the central issue of the war as the question of whether "states that voluntarily joined the Union by ratifying the Constitution [could] voluntarily leave the Union," Land I Love takes a broader view:

While Southerners were outraged by what they considered an abuse of their states' rights, many Northerners were grieved and angered by the practice of human bondage in their land. Thus both sides fought for values they held dear -- the North for national unity and freedom for all men, and the South for states' rights and the defense of their homes and families.

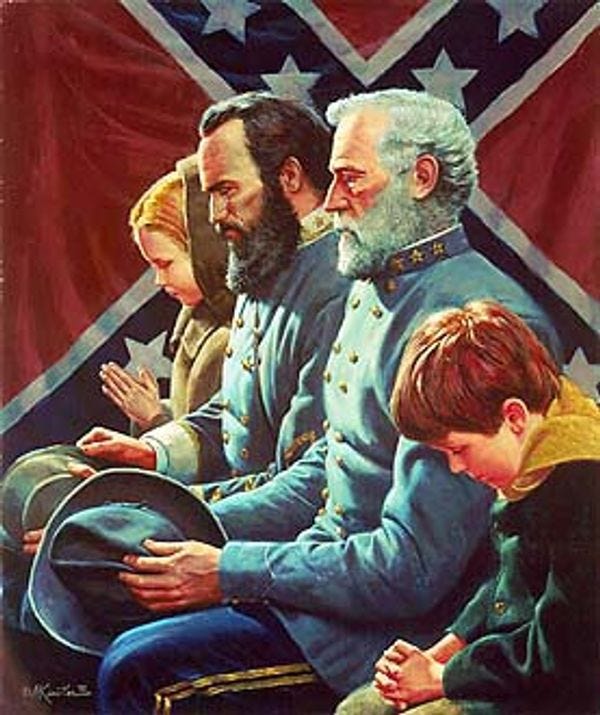

And that's about all the analysis the authors figure an eighth-grader can handle. On the other hand, they provide a full page on "Robert E. Lee: Great Christian General." For this age group, you really have to emphasize the important factual stuff.

In addition to its focus on states' rights that we discussed last week, U.S. History does acknowledge that slavery was kind of important:

While the institution of slavery was not the primary cause of the war, it was a highly charged, emotionally divisive issue among certain influential groups in the North and South.

You know, certain influential groups like the Southern legislators who voted to secede to preserve it. They were definitely influential. On the whole, U.S. History does whatever it can to diminish the idea that feelings about slavery were especially heated:

In the North abolitionists had made gradual gains in public opinion, at least in opposition to the expansion of slavery [in the territories]. Of course, racial prejudice in the North and fear of the impact of emancipation on the job market made many Northerners indifferent to the plight of blacks in bondage. Nonetheless, the moral high ground of moderate abolitionists ... was difficult to ignore. There was an obvious contradiction between "the proposition that all men are created equal" and the institution of slavery.

The discussion of the Southern states starts off with a sentence that only could have been written by a white guy:

In the South opinion on slavery was as varied as its people. The overwhelming majority of Southerners did not own slaves. Of the minority who did, most had but a few field hands or a house servant. Large plantations with large numbers of slaves were concentrated in the tobacco and cotton belts of the South and comprised only a fraction of Southern households; yet it was an influential fraction. These wealthy planters with their tremendous investments in their labor force felt threatened by abolitionist talk. Southern leaders reacted angrily to what they viewed as Northern interference in their lives. Some even went to lengths to defend slavery as a positive good. These radicals coupled with Northern radicals dominated public debate and poisoned it at the same time.

So yes, it turns out that it's the wealthy elites who were most influential. The book has no love for these particular job creators. Ultimately, says U.S. History, the war was caused by hotheads on both sides:

The Civil War resulted from a leadership failure that permitted extremists to take the terms of debate to their own ends.

Once the cannonballs start flying, both books present a fairly straightforward narrative of the battles and campaigns, with relatively little political or religious commentary -- the most notable exception is an almost offhand comment in U.S. History's section on the military and industrial capabilities of North and South:

In general, the Southern soldier took up arms for clearer, more compelling reasons than his Northern adversary. The Confederate was fighting to protect home and family from an invading force, which over the long term provided a more driving motivation in the face of death and deprivation than the Northern soldier’s effort to preserve the abstract concept of union.

We'd just like to note that Bob Jones University Press is headquartered in Greenville, South Carolina.

For the most part, neither book makes any claims about God's personal intervention in any phase of the war; nor does either mention Lincoln's comment in his Second Inaugural Address that both sides "read the same Bible and pray to the same God, and each invokes His aid against the other." Land I Love does take pains to remind us that Lincoln "revered the Bible" and read it regularly, and presents an anecdote that we're unable to find any verification for:

When asked why he stood while everyone else kneeled to pray, Lincoln humbly replied, "My generals always stand when they enter my office as I am their Commander-in-Chief. I think it is the very least I can do to stand when in the presence of my Commander-in-Chief."

It's in a history book, so it has to be true.

Both books present glowing profiles of Christian generals in the Confederate army; Land I Love has its page on Robert E. Lee, which seems to build its case that he was "a man of prayer" and a "Great Christian General" on the fairly conventional closing of a letter he wrote to his sister:

May God guard and protect you and yours, and shower upon you everlasting blessings, is the prayer of your devoted brother, R. E. Lee.

The section also emphasizes Lee's conflicted loyalties -- Lincoln offered him command of the Union forces but he finally decided he could not "raise my hand against my relatives, my children, my home" of Virginia -- and emphasizes that he was a moderate of sorts:

General Lee actually opposed slavery and freed all of his slaves ... He always insisted that the South would have voluntarily abandoned slavery if Northern radicals had not made the situation dangerous by encouraging slave revolts.

Update: Thanks to commenters Chichikovovich and TomAmitai for pointing out that this, too, is pretty much a lie: As executor of his father-in-law's will, Leeextended the bondage of George Washington Parke Custis's slaves to the maximum length allowed by the will -- an additional five years beyond Custis's death -- and was as cruel as they came, per the testimony of escaped slave Wesley Norris. This additional information makes the closing lines of the textbook's section on Lee, which we had cut to save space, especially galling:

Just as President Lincoln represented the best of the North, General Lee represented the most noble qualities of the South.

For its part, U.S. History has a text box titled "Stonewall Jackson: Soldier of the Cross," which informs us that Jackson "was converted to Christ shortly after he served in the Mexican War" and that his "courageous faith in God carried him through many dangerous battles":

For example, after First Manassas an aide asked General Jackson how he managed to remain so calm as bullets and shells whistled about him. Jackson replied, "Captain, my religious belief teaches me to feel as safe in battle as in bed. God has fixed the time for my death. I do not concern myself about that, but to be always ready no matter when it may overtake me." He paused and then added, "Captain, that is the way all men should live, and then all would be equally brave."

You have to admit it's a bit more inspiring than Robert Duvall walking through a similar scenario and wanting to go surfing, though perhaps no less delusional. Another great Christian trait of Jackson is that he attributed victories to God, which the text seems to think is something unique:

After the Second Battle of Manassas, an officer on the general’s staff said, "We have won this battle by the hardest kind of fighting." Jackson disagreed: "No, No, we have won by the blessing of Almighty God." After victory in the Battle of Port Republic during the Valley Campaign, Jackson turned to General Richard Ewell and said gently, "General, he who does not see the hand of God in this is blind, Sir, blind!"

Even better, Jackson "cared for the spiritual needs of his men as well," holding regular religious services, praying before making major decisions, and carrying "saddlebags of religious tracts for his men" -- but sadly, the little comic-book versions were still a century away.

Jackson's death is portrayed as something straight out of one of those Sunday-school books that Mark Twain satirized in "The Story Of The Good Little Boy," lacking only a scene of "everybody crying into handkerchiefs that had as much as a yard and a half of stuff in them":

After Jackson received his mortal wounds at Chancellorsville, his calm faith and composure deeply impressed those who attended him on his deathbed. He said, "You see me severely wounded, but not depressed, not unhappy. I believe it has been done according to God’s holy will, and I acquiesce entirely in it." When told that he was dying, Jackson took the news calmly. A little later he said, "It is the Lord’s Day ... My wish is fulfilled. I always wanted to die on Sunday." On Sunday, May 10, l863, Stonewall Jackson said quietly, "Let us cross over the river, and rest under the shade of the trees," and then he died. He left behind the testimony of a man who combined unflinching bravery with unflinching faith. As his wife said after Jackson’s death, "The fear of the Lord was the only fear he knew."

The textbook has nothing to say about the actual outcome of the war, which suggests that perhaps the Lord changed His mind after clearly tipping His hand at second Manassas and Port Republic. We understand He can be pretty mysterious about football, too.

Next Week: The home front, Marching through Georgia, and Reconstruction: the plight of disenfranchised Southern whites

If a homeskool crazy revisionist parent repeats a lie enough, a socially isolated and brainwashed kid will believe it.

Children are our future...

I have certainly learned a thing or two about the Old Hickory dickery, Dok!