Sundays With The Christianists: American History Books To Shield Homeschoolers From Heresy

We have to admit that we are getting quite an education from our American History textbooks for Christian schools. Last week, for instance, we learned that slavery was unpleasant but had its benefits, like those pretty spirituals. This week, we'll look at the Second Great Awakening, a period of evangelical growth in the early 19th century, and at other popular religious enthusiasms of the time, which were nothing but twisted heresies. Be sure to take notes, because your immortal soul will be on the quiz.

Both of our textbooks agree that in the years following the Revolutionary War and the ratification of the Constitution, Americans allowed themselves to get spiritually lazy. Our 11th/12th-grade text, United States History for Christian Schools, (Bob Jones University Press), says with an almost audible sigh,

Deism was the "faith" of several American leaders. A deist believed that God created the universe, set it into operation, and then stood back to allow it to work. Deists denied the deity of Christ, the inspiration of the Bible, the reality of miracles, and any other belief that struck them as "superstitious" because they could not explain it by their own reason. Revolutionary War veteran Ethan Allen wrote one of the first American defenses of deism, a crude, anti-Christian work. Thomas Paine, author of Common Sense, wrote a more polished -- but no more orthodox -- exposition of deism, The Age of Reason. Other American leaders, such as Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin, at least leaned toward deism.

The horror! Our 8th-grade text, America: Land I Love (A Beka Book), doesn't mention that any of the Founders were tainted by Deism; instead, it condemns the era's "cold formalism, declining church membership, and a questioning of Scriptural truths at institutions of higher learning" and declares that by the end of the 18th century, "America was in desperate need of spiritual revival."

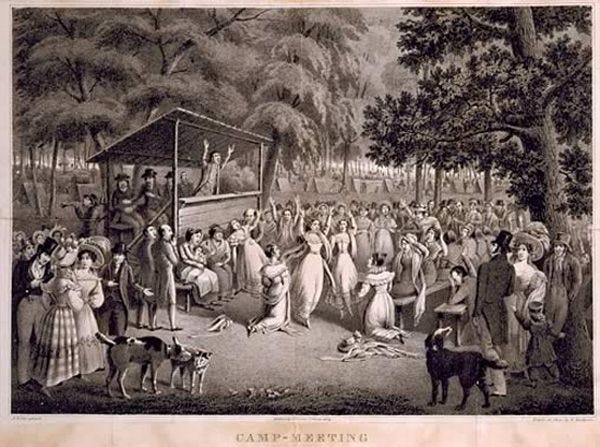

Happily, along came John Wesley and the Methodists, and circuit riders, and camp meeting revivals; one of the biggest of these, at Cane Ridge, Kentucky, between 10,000 and 25,000 converts, according to U.S. History (not surprisingly, Land I Love mentions only the higher number). Sunday schools and foreign missions also expanded, and we learn that one of the central figures in the movement was Charles Finney, who later served as president of Oberlin College (the less said about its modern heresies, the better).

Land I Love seems desperately committed to letting us know what an enlightened, practical fellow Finney was on the issue of slavery:

Though Charles Finney opposed slavery, he did not support the radical movement to force the South to give up slavery. Finney preached that the best way to end slavery was for revival to change the heart of the slave holder ... Finney realized that there were no political solutions to the problem of slavery. He predicted that, without spiritual revival, any attempts to force abolition of slavery would lead to a bloody civil war.

Strangely, while Land I Love describes the Second Great Awakening as a huge success, that civil war happened anyway. Should have prayer harder.

And just as it trivialized slavery, Land I Love also puts a missionary bandaid on the genocide of Native America:

At that time, government officials realized that dignity, prosperity, and peace among the Indians depended on their learning Biblical principles. American missionaries helped native Americans in many ways, teaching them (1) to live in peace with other tribes, (2) to support their families through farming and other practical occupations, and (3) to read, especially the Bible. Before the missionaries came, alcohol abuse and tribal warfare threatened to destroy the native American culture. The work of the missionaries and the gospel they brought helped to preserve and sustain the true value of American Indian culture.

Wasn't that sweet of them! Oh, also, the whites really wanted their land. Land I Love even manages to put a positive spin on the Indian Removal Act of 1830:

Christian missionaries accompanied the Indians on theirlong journey to Oklahoma,called the "Trail of Tears." Many Cherokees were so discouraged that they were ready to lie down and die. The missionaries restored their spirits by preaching, baptizing new converts, allowing for rest on Sundays, and meeting many physical needs.God used the ”Trail of Tears" to bring many Indians to Christ.

That seems like a pretty good thing to teach to eighth-graders.

In addition to all the fun evangelism and missionaries, the books both note the rise of "Unorthodox Religion" ( U.S. History ) or "Challenges to Christianity" ( Land I Love ). Both books agree that Unitarianism and Transcendentalism were dangerous heresies; as usual, U.S. History at least makes a stab at an objective description:

Unitarianism denies the Trinity and therefore the deity of Christ. Jesus, to the Unitarians, was a great religious teacher, but He was only a man and His death provides no atonement for sin. Instead, Unitarianism teaches that men should simply live moral, upright lives in order to please God.

Land I Love underlines its evils a bit more pointedly:

Unitarians also denied man’s sin nature and taught instead that human nature is essentially good. They told people to follow the teachings of Jesus and the dictates of their own reason. They believed that human reason could solve all of man’s problems.

According to Land I Love, this "false religion" shouldn't scare anyone anymore, because "it eventually lost its following as the Second Great Awakening gained momentum in the 1850s." U.S. History notes, a bit disapprovingly, that Unitarianism's influence went beyond its numbers of adherents, "because many of the wealthy and prominent leaders of eastern society became Unitarians." Rather than suggesting it died out, U.S. History emphasizes that it was only popular with elitists:

The denomination experienced little growth outside of New England, however, causing one wit to remark that Unitarian preaching was limited to "the fatherhood of God, the brotherhood of man, and the neighborhood of Boston."

Both books seem about equally aghast at the human-centered optimism of Transcendentalists, particularly Ralph Waldo Emerson's belief in human perfectibility. Land I Love seems especially invested in mocking dirty hippies like Emerson and Thoreau:

Transcendentalists claimed to believe in social reform for the betterment of mankind, but most were too busy communing with nature to participate in any reform movements. They were good at criticizing society but did little to make it any better. Fortunately, few people accepted transcendentalism, and the movement eventually died out.

This, from the book that explained how God made slaves' lives better by granting them the gift of song.

The books close out their discussion of American Heresy with a brief discussion of "cults," defined by U.S. History as "groups that call themselves Christian but which deviate from orthodox doctrine on one or more points" and more emphatically by Land I Love as

counterfeit church groups that go under the guise of Christianity. Though cults differ greatly from each other, they all have one basic error in common -- they teach salvation by works rather than salvation by grace through faith.

Oddly, Land I Love goes no farther than naming a few cults (Mormonism, Jehovah's Witnesses, and Christian Science), while U.S. History mentions the Shakers and the Mormons, giving a brief history of each. Considering the target-rich environment for condemnations of heresy, the biggest surprise is that both books seem more interested in lambasting the Transcendentalists than the Latter-Day Saints; perhaps the editors decided it was safer to go after a school of thought that today is only studied in university English departments.

U.S. History closes with a brief discussion of a revival movement that ran through the eastern cities from 1857 to 1859, saying that it

came at an opportune time. Within two years of its close, the United States would go to battle against itself in the Civil War. The blessings that God so graciously shed upon the young nation in revival would help to sustain it in the fiery furnace of war.

It's a nice way to transition to the next chapter, we suppose, but it does rather leave aside the question of why God wasn't a little more generous with the gifts of wisdom or compassion that might have prevented the war. But here too, at least we got some really good songs out of it.

Next week: The Civil War. Can you guess which textbook has the heading "Patriot Leaders of North and South"?

I looked quickly at the dogs in the lower left corner of the illustration, and thought that the one dog was shown as sniffing the other's butt.

I certainly would have thought him dead, but according to wiki, the World&#039;s Foremost Authority is still kicking. There is, apparently, a <a href="http:\/\/www.imdb.com\/title\/tt1560959\/" target="_blank">biopic</a>.