Sundays With The Christianists: American History Textbooks For Happy Factory Urchins

We're going to skip a couple of chapters in our American history books for homeschoolers this week -- sorry, Andrew Jackson fanboys! (Quick recap: Gold Standard good but Bank of the United States bad; Trail of Tears sad but inevitable.) Instead, let's look at our textbooks' chapters on advances (always advances, you know) in technology and culture in the first half of the 19th century. As usual, the 8th-grade text from A Beka Book, America: Land I Love, is far more emphatic in letting us know where our sympathies should lie; its chapter "The Blessings Of Technology" almost sounds like the editors are looking for investors:

America witnessed many wonderful advances in transportation, communication, and industry in the 1800s. New inventions such as railroads, steamboats, telegraphs, and farm machinery transformed life for many American families.

United States History for Christian Schools, the more restrained 11th/12th-grade text from Bob Jones University Press -- a description we keep finding ourselves astonished to be typing -- elects to illustrate the pace of change by noting that while the 1815 Battle of New Orleans was fought two weeks after the Treaty of Ghent was signed, the trans-Atlantic cable in 1858 made international communication a matter of minutes, not weeks or months. (Also, please Tweet this article to all your Facebook friends.) All of which is to say, we'll once again mostly focus on Land I Love, because that's the richer vein of triumphalist crazy.

For the most part, both books present a gee-whiz record of thrilling achievements in technology 'n' industry: you got your canals, your steamboats and railroads, your more-efficient exploitation of natural resources. Running through it all, according to Land I Love, is a spirit of enlightened and very Christian self-interest. Family-owned farms prove the superiority of free enterprise, dontcha know:

Private ownership of the land (1) instilled a sense of healthy pride, (2) desire [sic] to make a well-earned profit, and (3) assured the discipline and responsibility of every family member. The Bible was the most-read book on the family farm, and Sunday was the Lord’s day, a day of family rest. Farm life was healthy and wholesome; no one went hungry, and everyone had sufficient clothes.

Family farms -- despite their faulty parallelism -- also offset some of the less pleasant realities of 19th Century America, though Land I Love seems almost loath to even admit that there were any problems in God's America:

Most people in the South were family farmers with no slaves.Only about 25 percent of the people owned slaves, and most of those had only a few. A farmer with slaves in the South might have two or three, and these slaves would eat at the same table and sleep in the same house as the rest of the family.

Neither book endorses or justifies slavery, of course -- but both do what they can to offset the cruelties of slavery with depictions of some nice slaveholders who at least had the decency to have qualms about owning other human beings.

Even in cities, away from the bosom of the family farm where everything was beautiful and nothing hurt, early 19th-century America was a pretty cool place for everyone! In New England, for instance,

"Yankee ingenuity" soon found ways to develop the region’s abundant water power, and the Puritan work ethic provided ready workers for the factories.

Child labor? Don't be RIDICULOSE, there's no mention of it! But Land I Love does give us a full-page text box titled "Christian Influences on Industry," which acknowledges that "early factories required hard work and long hours," but that was OK because of improvements to everyone's standard of living, except maybe those whose limbs got ripped off in machines now and then. The hero industrialist of the early 19th century was Francis Cabot Lowell, who generously "provided clean housing, healthful food, schooling, and wholesome recreation for his employees" -- even though he didn't have to! Lowell

brought the efficiency and virtue of the Protestant work ethic to the factory system through his concern for the spiritual and physical health of his employees. A descendant of the original Puritan settlers of New England, Lowell carried on the Puritan tradition of godly behavior at work and in the home. Francis Lowell employed mostly young women in his mills. The work was hard but not dangerous. No one was allowed to drink alcoholic beverages, and workers attended church.

We'll assume there was an "or else" in the first draft, don't you think? Oh yes, there must have been; the Font Of All Knowledge * notes:

The 1848 Handbook to Lowell proclaimed that "The company will not employ anyone who is habitually absent from public worship on the Sabbath, or known to be guilty of immorality."

Anyhow, working for the mills (which were neither dark nor satanic, because William Blake was a blasphemous English troublemaker) was pretty much a lark for the "Lowell Girls" before they embarked on their true careers as Mommies:

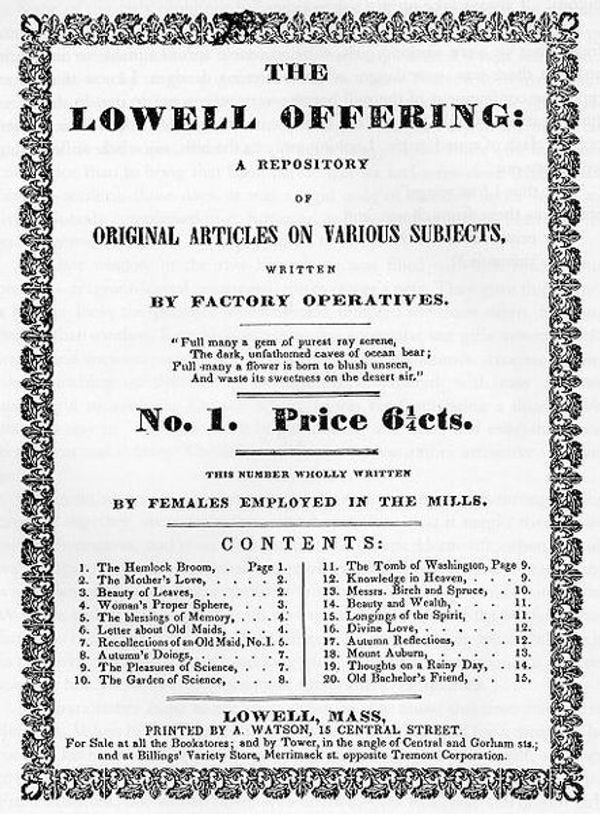

After working an average of 5 years in the mills, most of the women left to marry and start a family. At the factory, sisters and cousins often worked and lived together, for Lowell wanted to keep family ties strong. Some of the women who worked in the mills wrote and published a monthly magazine, the Lowell Offering. It included passages of Scripture which encouraged good behavior.

While Land I Love notes that even nasty socialist whiner Charles Dickens found the mills full of shining happy people, there's no mention that workers went on strike in 1834 and 1836 in response to wage cuts and rent increases, or that the mills also spawned an active "reform association" demanding regulations on working conditions. The reformers even published a radical little newspaper called The Voice of Industry, offering workers a point of view that was a bit less compliant and scripture-y than the Lowell Offering. Not to worry, those people don't belong in history books. Instead, just think about the achievements of Francis Lowell, who we are assured

believed that Christian principles could be applied to the modern age of industrialism, bringing benefits to the employer and his employees.

There's more, of course. Samuel Morse didn't merely invent the telegraph, he used Bible verses as his test messages! And after Darwin published On the Origins of Species,the filthy lies in that book were debunked by Louis Agassiz, who gets both bold and italics in his description as "America's greatest science teacher." Agassiz pretty much settled Darwin's hash in 1859:

As an accomplished student of the fossil record, he said that the fossil record contains no evidence for the change of one kind of living thing into another.

And that settles it. Oh, and in one final example of how government regulations are unneeded in a free market, we learn that when the happy (but poor, somehow) people in cities got tuberculosis from drinking "swill milk" -- from cows fed brewery and distillery waste -- technology and competition came to the rescue, because railroads could bring

"fresh milk from the farms at a much cheaper price than the "swill milk" sold by the breweries. Many young lives were saved or improved when railroads began to deliver fresh milk to the cities."

The question of why it was legal in the first place to sell milk that made children sick does not, of course, get asked. Rather, it's just one more example of how "God blessed America with technology and the ability to apply it to everyday life."

Next Week: Slavery, and why it was definitely bad, but not necessarily as bad as those liberal professors want you to think it was.

* The Wikipedia entry on the "Lowell Mill Girls" is pretty awesome, really -- well-sourced, engaging to read, and maybe just a little Howard Zinn-influenced. We mean that the good way.

I like <a href="http:\/\/www.pbs.org\/wgbh\/amex\/mwt\/gallery\/" target="_blank">A Midwife&#039;s Tale</a> for the late 1700&#039;s.

What a <i>writhing</i> pile of horseshit this is.

Fixed.