Sundays With The Christianists: American History Textbooks That Wonder Why God Let Pagans Get Here First

Greetings, Wonkademics! So glad you could roll up for our magical history tour! This week, we continue our look at two textbooks for homeschoolers and Christian schools, the 8th-grade text from A Beka Book, America: Land I Love, and Bob Jones University Press's backpack-burster for 11th/12th graders, United States History for Christian Schools. This time around, we'll look at how these books approach the story of how a just and merciful God brought civilization and smallpox to the original inhabitants of North America.

As we noted last week, Land I Love is the more aggressive of the two books when it comes to telling students that history is an account of how things turned out exactly like God planned. In a brief section on "America Before Columbus," we're reminded that the best history text is the Bible:

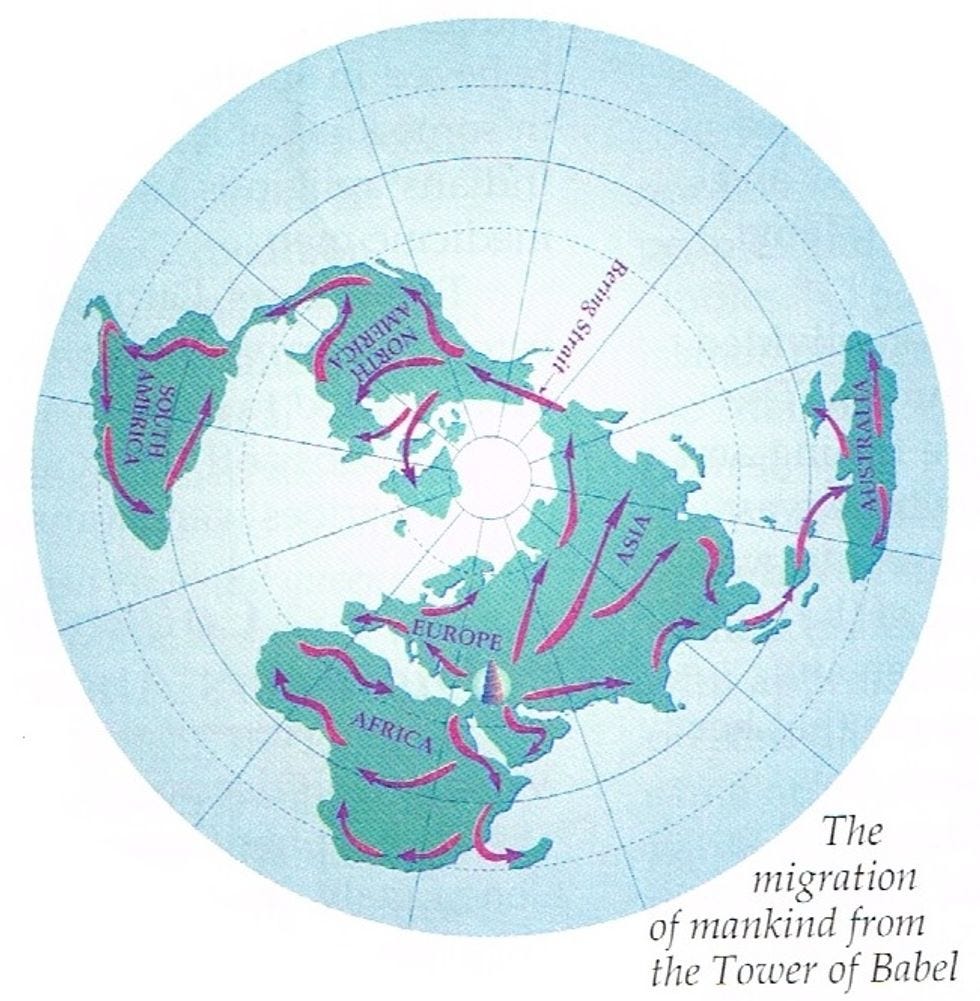

Over four thousand years ago, after the great Flood of Noah’s day, God caused the people of the world to speak many different languages and scattered them from the tower of Babel "upon the face of all the earth" (Gen. 11: 9). The ancestors of the native Americans left the tower of Babel to begin a great migration that eventually led to the area of the earth that we can theWestern Hemisphere,or theNew World.... To get to America, they may have walked over a land bridge -- possibly where the Bering Strait now separates North America and Asia. These continents could have been divided during the days of Noah’s great-great-great grandson Peleg, who was born 101 years after the Flood. Peleg’s name means "divided," and the Bible says that in his days the earth was divided (Gen. 10: 25).

Please disregard anything you might read about human migrations to North America between 50,000 and 15,000 years ago and remember that the Bible says it all happened last week. It only makes sense, because the first inhabitants of the New World "were probably hunters following the trail of the animals that had begun to multiply and spread out over the earth after the Flood." See? Facts and logic! There's even a Bible Science diagram, so you know that's how it all happened:

The Bob Jones text, on the other hand, merely says that human migration into North America occurred "some time after the Flood" and quickly moves on to factual stuff that they can more easily say with a straight face. Neither book is willing to condemn the paleolithic invasion of America as a blatant act of illegal immigration, an oversight that some smart publisher may be able to exploit.

Land I Love devotes a few neutral paragraphs to Native American agriculture and society -- without even condemning them as dirty pre-hippies -- before reminding us that there was nothing idyllic about their world:

The early American Indians, like most other people, had forsaken the things that their ancestors knew about God. Their stories about the Creation and the Flood were not accurate. They worshiped things they could not explain, like thunder, wind, fire, and the sun. They believed in spirits, both good and evil, and in some kind of life after death.

Silly primitives, believing inaccurate Creation stories!

U.S. History -- apart from that one mention of the Flood -- actually includes a chapter on the Eastern tribes that wouldn't be out of place in some secular textbooks. It even cautions readers that despite popular depictions, "American Indians were not backwards savages; they built societies of surprising complexity." Sure, it's ethnocentric, but it's far better than we'd have guessed from a Bob Jones book. U.S. History even discusses Native American religious beliefs without editorializing. We have to go back to Land I Love to find stuff to make fun of.

And with the arrival of the Spanish conquistadores, Land I Love happily obliges, giving us a detailed critique of why Aztec religious beliefs were Very Bad:

they had long forgotten the loving God Who created them and had exchanged Him for the cruel "gods" (forces) of nature. As one historian notes, "The Aztec religion had no savior, no heaven or hell to reward or punish the consequences of human behavior." Righteousness was judged solely by submission to the gods.

Also, human sacrifices, but happily, Cortés came along and enlisted the nearby tribes that the Aztecs had dominated, to "conquer the ruthless Aztecs and put an end to their bloody religious rituals." U.S. History, on the other hand, portrays Cortés as going rogue, disobeying his orders to explore only the Mexican coastline:

The great Aztec king Montezuma, hearing of the Spanish arrival, sent emissaries offering gifts that he hoped would be picked up like door prizes by these uninvited guests on their way home. However, the enticing gleam of turquoise masks, intricate gold figurines, and massive disks of hammered gold made Cortés decide he would rather try his hand at conquest than run errands for the govemor of Cuba.

It's not so much his wholesale slaughter of the Aztecs that raises the editors' ire, it's that disobedience to lawful authority.

Both textbooks attribute the failure of the Spanish colonization effort in the Americas to the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588 and the subsequent rise of English naval power; both are also quite happy to celebrate the defeat of Phillip II as a Big Win for Protestantism. On the topic of the Armada, U.S. History actually outdoes Land I Love in the vital field of Catholic-bashing, noting that before commanding the English fleet that defeated the Armada, Sir Francis Drake's raids on Spanish shipping brought him some sweet revenge against the papists:

There was much more to Drake’s daring raids than simply fame and fortune -- he sailed with blood in his eye against the Catholic threat. Drake’s father, a tenant farmer, was a fervent Protestant lay preacher who had a great influence in shaping his son’s character and convictions. When Drake was a boy, he and his family were forced to flee their home during a Catholic uprising. In order to escape, the family lived in the rotting hulk of a ship on the bank of the Thames. Ironically, the boy whom the Catholics forced to live in dire poverty in the hulk of a ship would one day take a ship and greatly enrich himself at the expense of Catholic Spain.

More importantly, both books agree, the defeat of the Armada -- in part by storms, and we know who's responsible for weather -- meant that North American colonization would be dominated by Protestants, as God intended. U.S. History even breaks with its usual reluctance to say Goddidit (at least out loud) and rejoices,

The defeat of the Spanish Armada ... secured the future for Protestants in England. Clearly, God was providentially preserving His witness in that country. In addition, it spelled the end of the Spanish century and the beginning of English dominance on the seas and eventually in North America.

And Land I Love puts it in italics, so you know it will be on the test:

Although Catholic Spain would continue to hold land in America for several centuries, she would not dominate the New World. Protestant England and Scotland would be free to lay the groundwork for political and religious freedom in North America.

And next week, we'll look at how well that religious freedom thing worked out in the Protestant colonies, where Puritans were free to cut off Quakers ears and drag them naked through the streets for their blasphemy. God wanted it that way!

"They worshipped things they didn't understand, like fire, and signs..."

Destroying a culture is HARD WORK.